The most common argument I hear from investors who aren't interested in dividends is that the company should be able to find something better to do with its cash than to give it back to shareholders. The most common argument I hear from investors who aren't interested in dividends is that the company should be able to find something better to do with its cash than to give it back to shareholders.

They say that the funds should be used to grow the business either by investing in the business itself or by acquiring new ones.

As Vice President Joe Biden would say, "That's a bunch of malarkey!"

Let's look at why that argument doesn't hold water.

Obviously, I'm not opposed to a management team investing in its business for growth or even buying other companies if it will add to long-term profitability and cash flow.

But often, executives spend shareholders' capital on ill-fated acquisitions because the money is there.

In my book Get Rich with Dividends , I mentioned a discussion I had with Community Bank Systems (NYSE: CBU) CFO Scott Kingsley. He explained to me why the company has a policy of consistently returning capital back to shareholders in the form of dividends.

He said, "We are very 'capital efficiency' conscious. We believe 'hoarding' capital to potentially reinvest via an acquisition or some other use can lead to less-than-desirable habits."

He went on to say that because of the company's dividend policy, when management wants to make an acquisition, it usually must go to the capital markets for financing, which forces them to closely examine whether the transaction really makes sense.

Let's Make a (Bad) Deal

How many horrible acquisitions can you name?

Chances are, management made them because it had the cash on hand, so what the heck? Gotta spend it on something, right?

In 1994, Quaker Oats (now part of Pepsi) bought Snapple for $1.7 billion. Just three years later, the company sold Snapple for $300 million, losing 82% of its investment. That means that $25 per share of Quaker Oats' shareholders' money went out the door and into the pockets of Snapple's owners.

Would Quaker Oats' shareholders have preferred a dividend instead? I'm not a mind reader, but I'm going to guess yes.

Similarly, in 2007, Clorox (NYSE: CLX), which does have a solid track record of returning cash to shareholders, paid $925 million to acquire Burt's Bees. Four years later, it took an impairment charge on the acquisition of $250 million or $2 per share. Would Clorox's shareholders have appreciated a $2 per share dividend? I'm sure they would have.

Now, that doesn't mean Clorox would have issued a $2 dividend had they paid the right price for Burt's Bees, but you can see that companies can be easily tempted to spend shareholders' money, no matter the price, in order to land a prized acquisition.

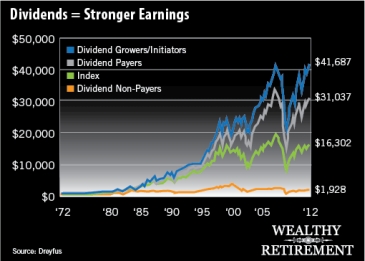

Dividends = Stronger Earnings

Studies have shown that companies that pay dividends have more reliable earnings than those that don't.

Douglas J. Skinner and Eugene F. Soltes, professors at the University of Chicago and Harvard University respectively, concluded, "We find that the reported earnings of dividend-paying firms are more persistent than those of other firms and that this relationship is remarkably stable over time. We also find that dividend payers are less likely to report losses and those losses that they do report tend to be transitory losses driven by special items."

So non-dividend payers may use their cash to acquire growth, but the dividend-paying companies have stronger and more consistent earnings. And a vital rule of investing is stock prices follow earnings.

If earnings are better and more reliable for dividend-paying companies, that should mean dividend-paying companies' stocks perform better.

And we know that they do.

View larger image

The above chart shows that companies that grow their dividends outperformed the general market by 155% over the past 40 years. While the stocks that did not pay dividends barely budged over the same time period.

Dividend stocks beat the pants off of those that don't pay dividends, while at the same time shareholders receive income while their stocks are in the process of issuing said beating.

So the next time a friend says a company should have better things to do with its cash than pay dividends, wish them luck with their investing and just know that you'll likely be picking up the tab for lunch in a few years - because you'll be the one who can afford it.

Best,

Marc Lichtenfeld

Chief Income Strategist, The Oxford Club |

|

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)