A time the KKK 'tried that in a small town'.....

Post# of 128874

The time Notre Dame students chased the KKK out of town, and destroyed their HQ with potatoes

This is such a great story about resisting evildoers. Enjoy

It was May 1924, and the Ku Klux Klan wanted to showcase its power and cement its sudden grip on Indiana politics by holding a picnic and parade in South Bend, the most Catholic area in the state.

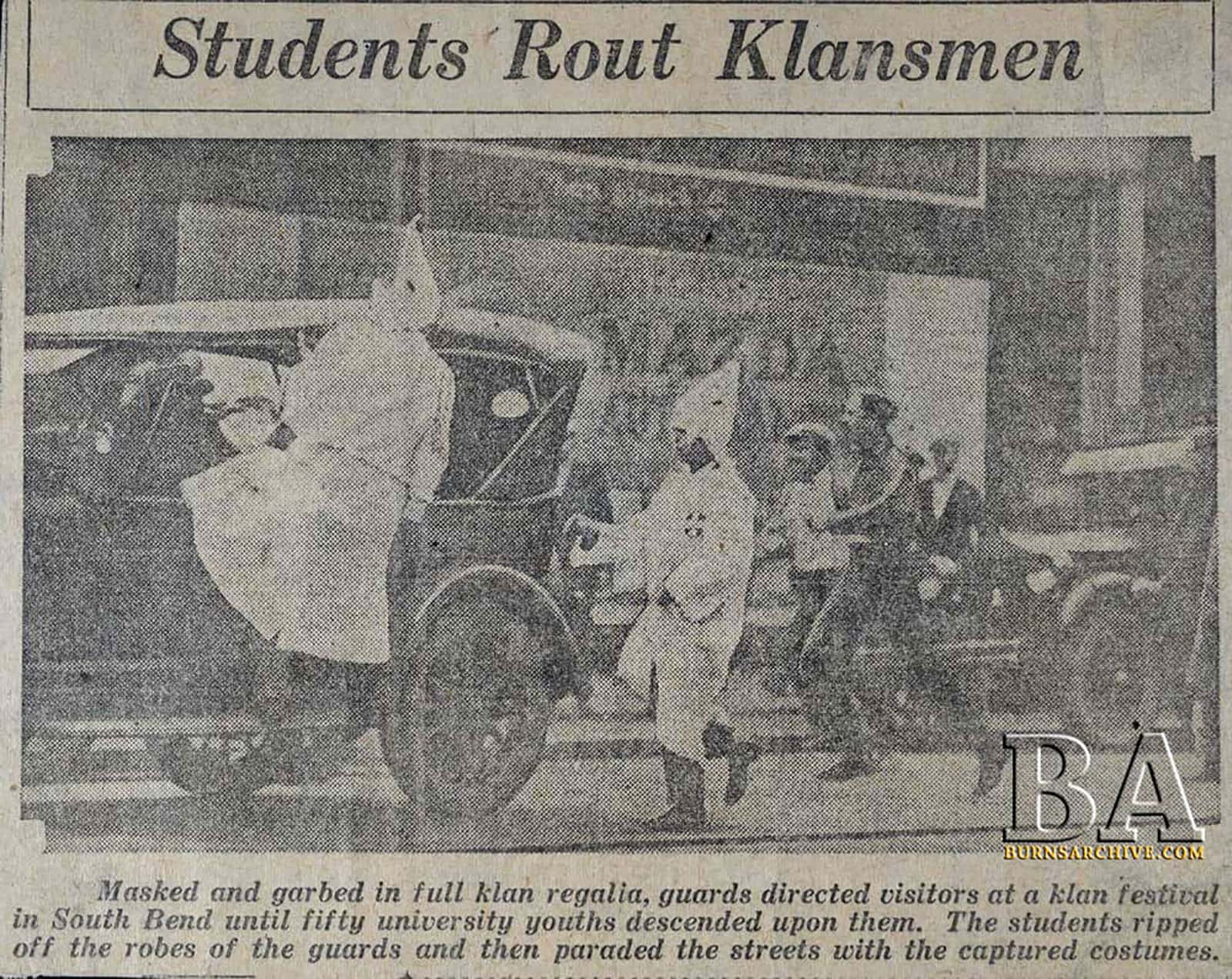

About 500 University of Notre Dame students showed their objections by storming downtown and ripping the hoods and robes off surprised Klan members. As the Klan arrived in trains, buses and cars, the students roughed members up in alleys and stole their regalia for battle trophies. They chased the rest to the Klan headquarters downtown at the corner of Wayne and Michigan streets.

https://www.nd.edu/stories/a-clash-over-catholicism/

Newspaper clipping from the Chicago Herald and Examiner, Sunday May 18, 1924. (Stanley B. Burns, MD and The Burns Archive).

A “fiery cross” made from red light bulbs shined in the office’s third-floor window. By a stroke of luck, a store selling groceries on the ground floor had barrels of potatoes outside. The students began launching the potatoes, breaking the window and then all of the lights but the top one. Their arms ragged, no one seemed to be able to reach the last taunting bulb.

The crowd called forth Harry Stuhldreher, the football team quarterback who would be immortalized five months later as one of the Four Horsemen. He reared back and let loose a potato from his cannon of an arm. The crowd leaned in as it traced a perfect arc … and went wild when the light bulb exploded in a shower of sparks. Just kids having a rip-roaring time.

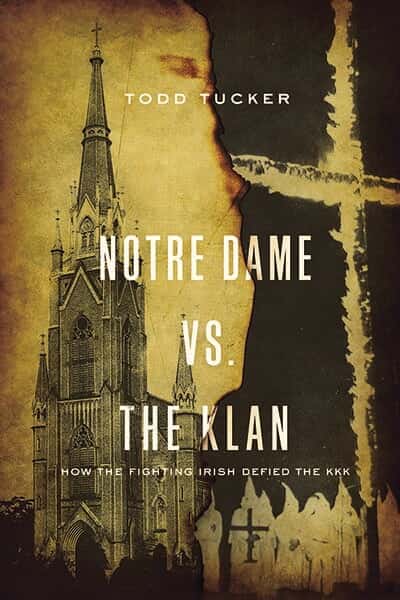

The front cover of the book by Todd Tucker reads 'Notre Dame vs. the Klan, How the Fighting Irish defied the KKK.' It depicts the Bascilia beside a fiery cross.

The students were so exuberant that they rushed up the steps toward the third-floor office. At the top of the first flight, a wild-eyed man who said he was a Baptist preacher jumped out and stuck a pistol in the chest of Bill Foohey, a sophomore from Fort Wayne, Indiana. The students retreated down the stairs and regrouped.

This quick turnabout in some ways encapsulates the riotous confrontation between the Klan and Notre Dame students in 1924. It represents the students’ free-spirited success in facing down hatred, but then gave way to the real dangers of a violent anti-immigrant fervor that swept through Indiana and much of the nation and focused its hate on both Catholics and the Irish.

The parallels to the violent clashes in Charlottesville, Virginia, one year ago are inescapable. In fact, Notre Dame Press decided to republish this month in paperback a book about the event, “Notre Dame vs. the Klan,” by alumnus Todd Tucker ’90. In the end, the students’ unwillingness to back down to bigotry had a lasting effect: The Klan never fully took over South Bend, scrapping a planned second rally and fading quickly.

The Notre Dame administration was at first embarrassed by the stereotype of its Catholic students throwing potatoes and brawling, but it also never disciplined a single student for standing up to the Klan. Plenty of misinformation and “fake news” distort today’s viewpoint of this long-ago confrontation, but a closer look may bring important context into better focus.

The Indiana Klan

While it’s true that Indiana became the heart of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s — at one point claiming about one in every three native-born white males as members — the facts don’t tell the whole story.

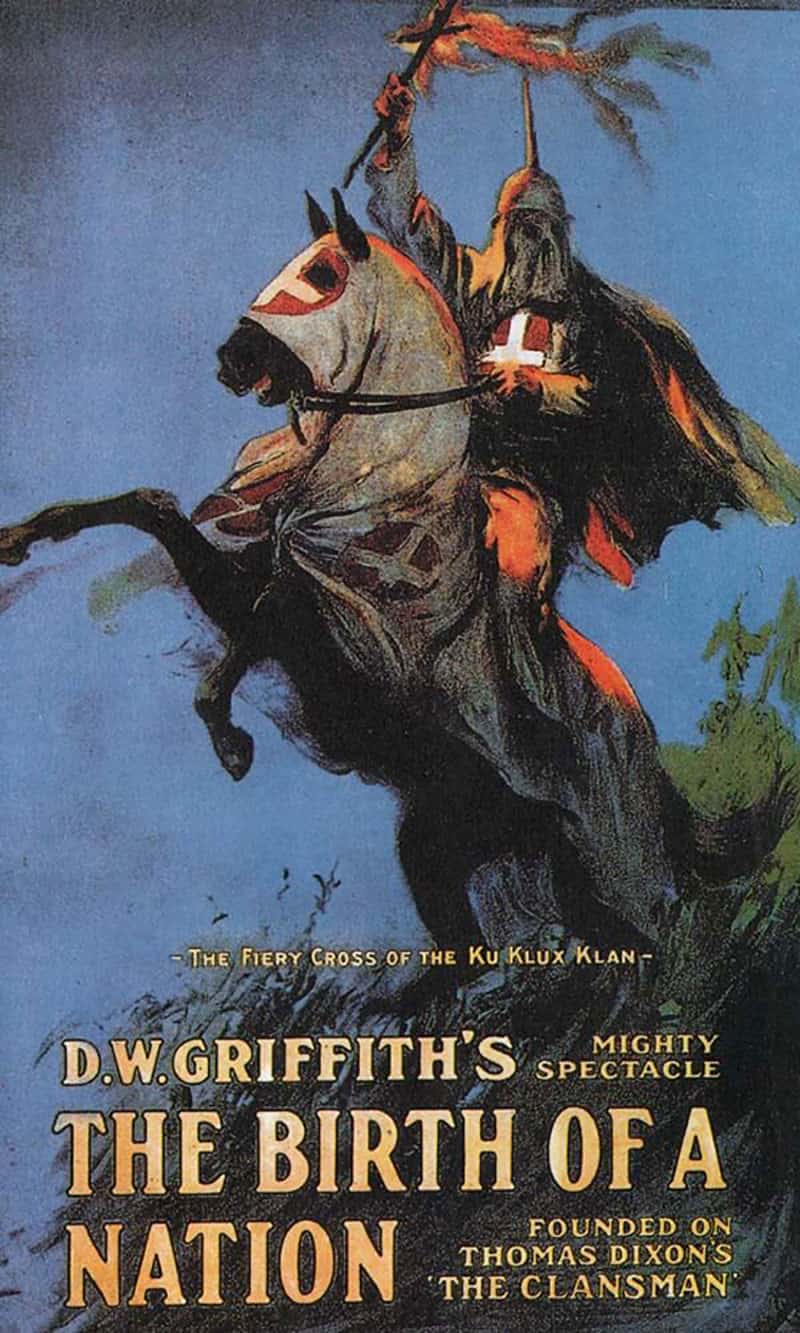

The Klan had arisen in the South after the Civil War as a violent response to the emancipation of slaves, but that version had largely died out. Its revival began in 1915 with the first big-budget movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” which depicted the Klan as a patriotic force protecting the nation’s decency and honor.

The conditions under which the Klan flourishes have always been the same: Times of great social and religious change bring about a fear of outsiders and immigrants, provoking a reaction marked by nativism and ripe for populist exploitation. The rise of communism, Irish immigration and the threat of war contributed additional fear in the Roaring Twenties.

But what made Indiana unique was that one man, D.C. Stephenson, engineered the Klan’s revival in the state. He was not a true believer or a racist ideologue, but he was a talented salesman and opportunistic huckster who saw a chance to exploit people’s fear and nationalism for profit in 1921.

Instead of a secret society dedicated to nighttime violence, Stephenson sold this gentler Klan as an all-American social fraternity that gathered for picnics and parades, complete with high school bands and free barbecue. The speeches and newsletters focused on patriotism and virtue.

In less than three years, Stephenson grew the Indiana membership to more than 425,000 people, more than that of Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia combined. As Grand Dragon, his cut of the $10 Klan membership fee made him rich, and he used his money and contacts to gain political power.

“It was a campaign of hate for the purpose of raising money.”

— Rev. Arthur Hope, C.S.C.

Rev. Arthur Hope, C.S.C., author of “Notre Dame — 100 Years”, put it this way in his 1948 history of the institution: “The impetus from which arose this intolerance was not ignorance itself, but a shrewd and calculating resolution, on the part of men who knew better, to play on the ignorance and bigotry of the masses who did not, we believe, know better. It was a campaign of hate for the purpose of raising money.”

A Klan parade in New Castle, Indiana in 1922. (Indiana Historical Society, PO411).

At one point, the Indiana Klan even reached a deal to buy Valparaiso University and create a “100 percent American curriculum.” The deal fell apart when the Klan’s national leadership backed out and the struggling school was embarrassed by the news reports.

Stephenson’s quick rise hit its zenith in 1924, when he engineered a Klan takeover of the state’s powerhouse Republican Party. His sales savvy included the distribution of the Klan’s political slate on a single sheet of paper, rolled and tucked into a wooden clothespin and delivered to thousands of Hoosier doorsteps. His tactics proved successful when Ed Jackson, an open Klan member, became governor that year. Other Klansmen won elections for the mayor of Indianapolis, its entire council and other positions across the state.

Stephenson may not have been a true ideologue, but he was a relentless egomaniac in his power-broking, drinking and womanizing, which would finally lead to his downfall.

The Resistance

In Indiana, the 1920s Klan did not target black people as “the other” because there weren’t many. Instead, its nativist anger focused on the threat of Catholicism, which was widely mistrusted as an anti-American force taking orders from foreigners in the Vatican. Notre Dame sewers were rumored to harbor an arsenal for a Catholic uprising.

A famous incident in 1920 reveals the animus of the time. Before football star George Gipp died — around the same time he reportedly asked Coach Knute Rockne to win one for the Gipper — he became a Catholic on his deathbed. His devout Baptist family was so angry that he converted while delirious that they refused to let any priests or school officials attend his funeral. The controversy was cited as another example of sinister Catholic rituals.

One Klan speaker in South Bend struck students as harmless until he said immigration was out of control and that Catholics can’t be “good Americans,” according to Tucker’s book.

A Chicago attorney, Patrick O’Donnell, started a magazine named “Tolerance” to fight the Klan’s anti-Catholic propaganda. One of his methods was to find lists of Klan members and publish their names, highlighting the prominent ones. This led the Klan to plant fake lists in an attempt to embarrass O’Donnell and trigger lawsuits.

One list included the Notre Dame barber, prompting a group of enraged students to destroy his shop and equipment. Later false lists hit higher, including some lay professors and the chairman of the Board of Lay Trustees.

Rev. Matthew Walsh, C.S.C., then the University president, largely ignored the Klan until it planned a three-day rally starting on May 17, 1924. The reticent World War I chaplain sent representatives to meet with Larry Lane, the South Bend police chief, the day before.

Rev. Hugh O’Donnell, C.S.C., the prefect of discipline, understood the danger. “You can appreciate my position, Chief Lane,” he said, according to his written report to Walsh, “in trying to keep two thousand red-blooded young men on campus when an occasion like this presents itself.”

Lane assured the priests that the city would not grant the Klan’s parade permit. Still, Walsh wrote a bulletin and posted it around campus, urging the students to ignore the meeting and stay on campus.

The Riot

On the Saturday morning of the Klan meeting, off-campus students arrived with talk about robed Klansmen directing traffic on every street corner downtown.

With little debate, about 500 enraged students ran the two miles to the city. In his University history, Hope describes each Klan member arriving carrying “under his arm a suspicious bundle.” He says the students greeted them kindly and offered to show them to the parade. “Up an alley, down a side street, through a dark entrance, and a Klansman would emerge without his sheet, and sometimes with a black eye.”

Tucker writes that Bill Foohey, the grandfather of one of his dorm friends, won renown by stealing a robe and hood, wearing them as a prize in a photo afterwards. Foohey didn’t find it as funny when the preacher threatened him with a pistol.

To resolve that threat, a group of seniors spoke with Klan leaders and reached a compromise: the Klan could parade only if they didn’t wear robes or carry guns. Instead, a rainstorm ended the picnic and foiled the parade. But rain didn’t stop the students, who continued to harass Klan members and drive many out of town.

No one was seriously hurt and only eight arrests were made, six of them students, including two for using profane language. Father Walsh was disappointed that news reports portrayed the students as brawling rioters, living up to a stereotype that would hurt the school’s reputation.

Lane was even more upset about reports of lawlessness in his city. He vowed not to let it happen again, while the county sheriff deputized about 30 Klansmen. They did not have to wait long for their opportunity.

On Monday night, a phone call to Freshman Hall said that the Klan had one student and was beating him mercilessly. Again, about 500 students rushed to town — and into an ambush. Near the Klan office, the students encountered a group that included prepared Klansmen, the police and the sheriff’s deputies.

Bottles and rocks flew through the air. Bats and police clubs cracked down on skulls and backs. The students fought back, throwing punches and organizing into flying wedges like the football team. Bloody and bruised, many of them retreated to regroup at the county courthouse a few blocks away.

“Whatever challenge may have been offered tonight to your patriotism, whatever insult may have been offered to your religion, you can show your loyalty to Notre Dame and to South Bend by ignoring all threats.”

— Rev. Matthew Walsh, C.S.C.

Father Walsh arrived then. A historian cognizant of Father William Corby’s blessing on a large rock before the Battle of Gettysburg, Father Walsh mounted a cannon on the courthouse lawn to speak.

“Whatever challenge may have been offered tonight to your patriotism, whatever insult may have been offered to your religion, you can show your loyalty to Notre Dame and to South Bend by ignoring all threats,” Walsh bellowed, according to newspaper reports and Hope’s book. “A single injury to a Notre Dame student would be too great a price to pay for any deed or any program that concerned itself with antagonisms. I should dislike very much to be obliged to make explanations to the parents of any student who might be injured — or even killed.”

Indeed, the amazing thing was that no one was killed that night. The students heeded their president’s direct command and marched back to campus.

The Aftermath

While Walsh and the University never disciplined the students, there were lectures and pledges not to riot again. Coach Rockne wrapped up a rambling speech by telling them that a football team must follow its quarterback.

“Father Walsh is your quarterback, and you are the great Notre Dame team,” Rockne said. “It is your duty to follow the signals of Father Walsh, and when you do, you will be in the right, and will not be a party to any disorder.”

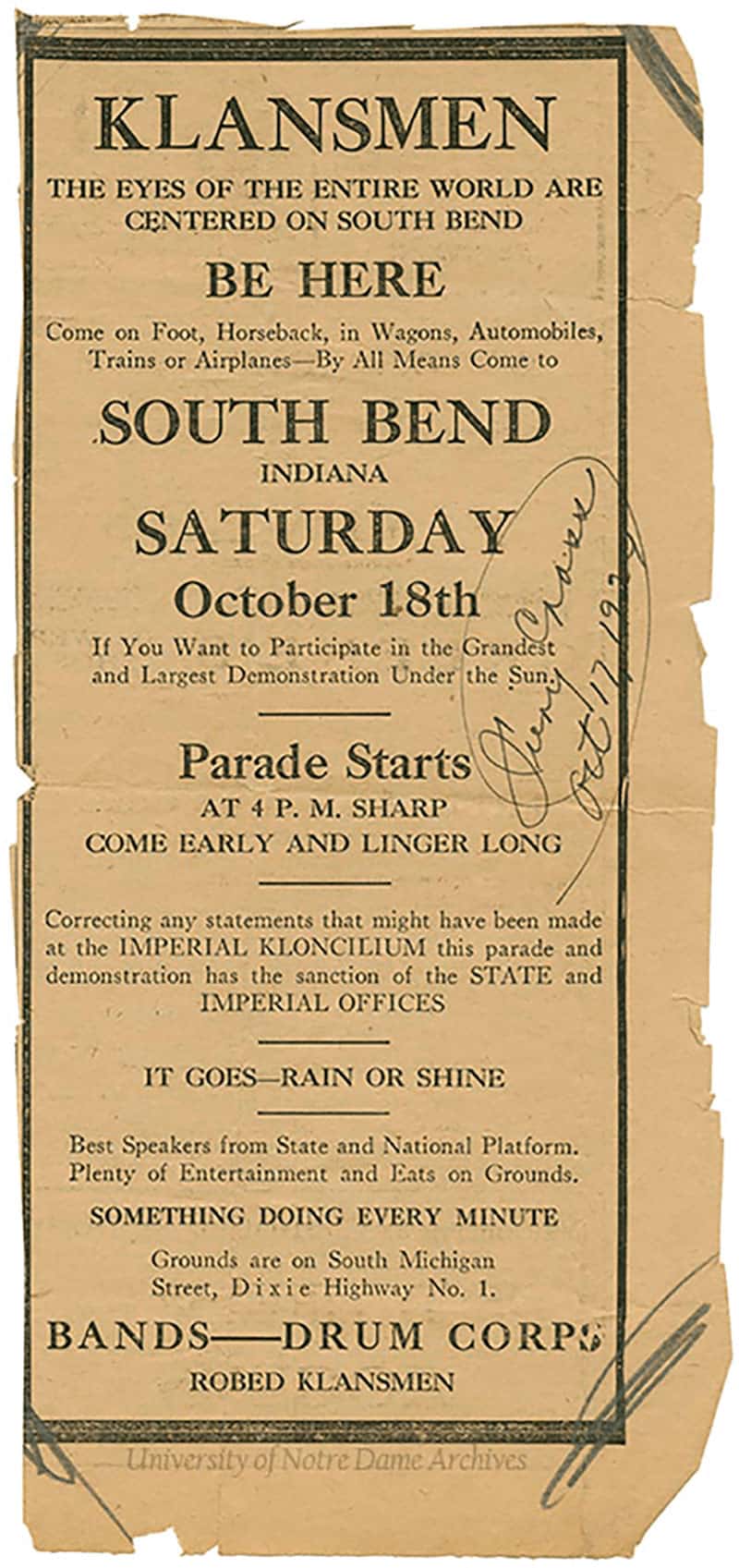

Handbill reads, 'Klansmen, the eyes of the entire world are centered on South Bend. Be here. Come on foot, horseback, in wagons, automobiles, trains or airplanes — by all means come to South Bend, Indiana Saturday, October 18th if you want to participate in the grandest and largest demonstration under the sun.', followed by event details.

The Klan revved up its propaganda machine, reporting that student hooligans attacked women, beat up peaceful Klansmen and trampled American flags. One Klan report even claimed that a student pulled a baby out of a carriage, smacked it across the face and threw it at the mother.

Most mainstream reports were more even-handed. The South Bend Tribune headline read, “Klan display in South Bend proves failure.” A St. Paul headline read “Notre Dame Students Clash with Kluxers.” But a Youngstown, Ohio, editorial railed against the students as “papal pirates” and asked whether this was Ireland or America, suggesting the “street blackguard” get a “retributive horsewhipping.”

The propaganda and rumors had some effect. Walsh received many letters requesting explanation and one letter promising “hot lead” for any students who leave campus. Another railed against “Mackarel Snapping hoodlums” and made veiled threats against campus buildings, while a later report claimed that a Klan member at one meeting offered to dynamite Notre Dame.

Walsh filed it all away, resolved to ignore it and let the anger peter out on its own. D.C. Stephenson unwittingly helped this come true when he was convicted of second-degree murder for kidnapping and raping a woman who then committed suicide.

The Klan planned another rally in South Bend in October, openly promising revenge. A handbill was printed up. But with its salesman in jail and politicians becoming embarrassed to be associated with the Klan, it never happened.

Tucker, the Klan story’s chronicler, lives and writes in Valparaiso, Indiana. He said the recent re-emergence of white supremacism and the Klan have clear parallels in the history he researched. Klan members even showed up during his book tour in 2004.

“The Klan is a very durable American institution,” Tucker said by phone. “One of the reasons it’s durable is because it’s adaptable. It doesn’t surprise me at all to find them at the front of the mob. Fear of immigrants, fear of change — that we’re changing for the worse. And an ability to capitalize on those fears — they’ve always been really effective at that.”

At Notre Dame, Father Walsh addressed the immediate threat. Unhappy that most Notre Dame students lived off campus and were vulnerable, he embarked on a building spree that included South Quad dorms and South Dining Hall. The students had fought their way home. Maybe it’s no coincidence that it was Father Walsh who in 1927 finally authorized the “Fighting Irish” as Notre Dame’s official nickname.

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)