Geolocation 101 This 2019 article from The NY T

Post# of 128895

This 2019 article from The NY Times is a good backgrounder on cell phone geolocation. It will help dispel some of the ignorant nonsense being disseminated on this topic by the ignorant Left.

ONE NATION, TRACKED

AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE SMARTPHONE TRACKING INDUSTRY FROM TIMES OPINION

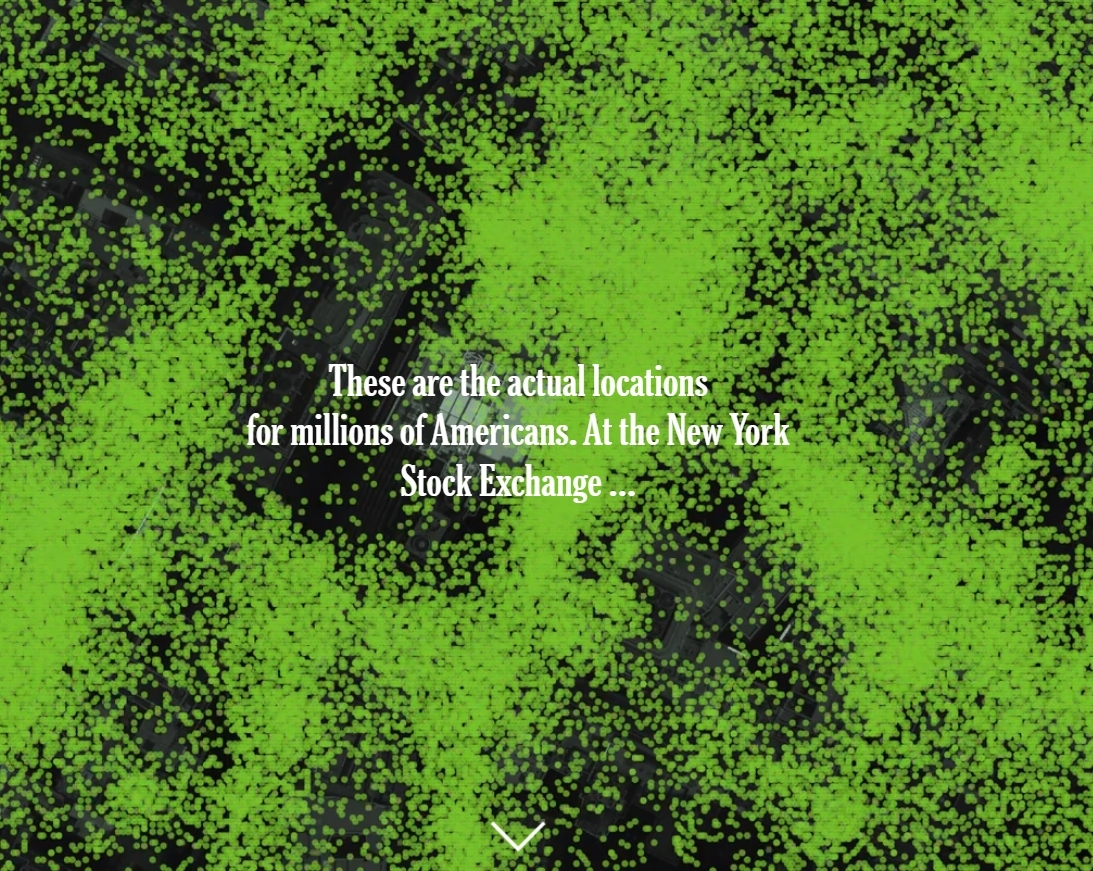

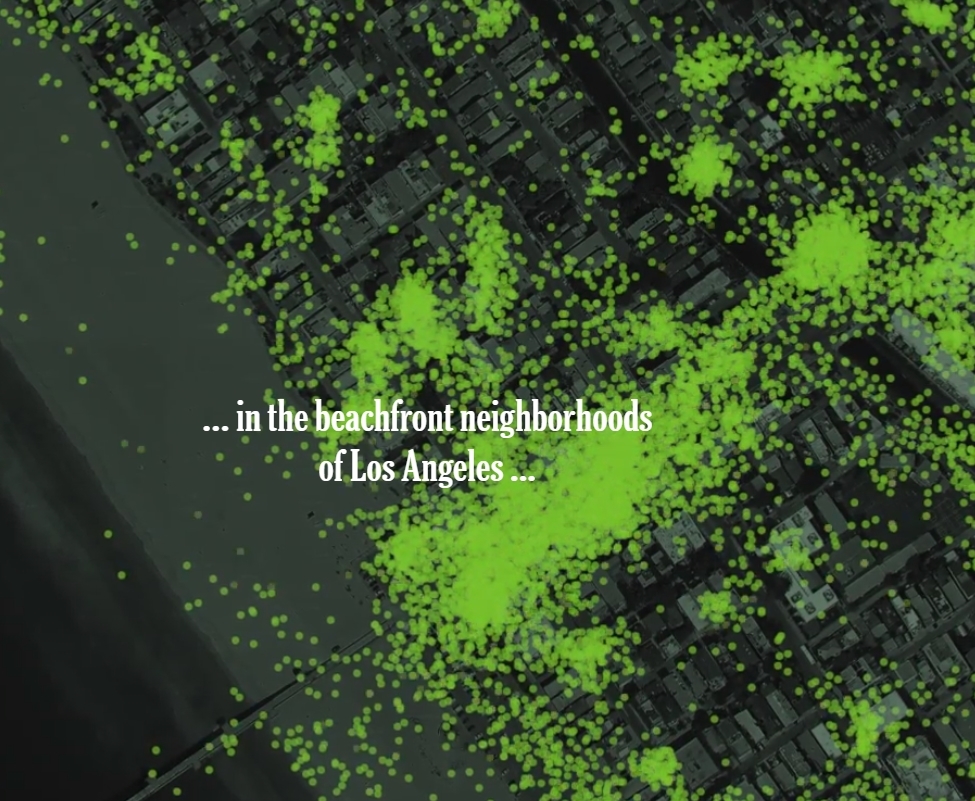

EVERY MINUTE OF EVERY DAY, everywhere on the planet, dozens of companies — largely unregulated, little scrutinized — are logging the movements of tens of millions of people with mobile phones and storing the information in gigantic data files.

The Times Privacy Project obtained one such file, by far the largest and most sensitive ever to be reviewed by journalists.

It holds more than 50 billion location pings from the phones of more than 12 million Americans as they moved through several major cities, including Washington, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Each piece of information in this file represents the precise location of a single smartphone over a period of several months in 2016 and 2017.

The data was provided to Times Opinion by sources who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to share it and could face severe penalties for doing so.

The sources of the information said they had grown alarmed about how it might be abused and urgently wanted to inform the public and lawmakers.

After spending months sifting through the data, tracking the movements of people across the country and speaking with dozens of data companies, technologists, lawyers and academics who study this field, we feel the same sense of alarm. In the cities that the data file covers, it tracks people from nearly every neighborhood and block, whether they live in mobile homes in Alexandria, Va., or luxury towers in Manhattan.

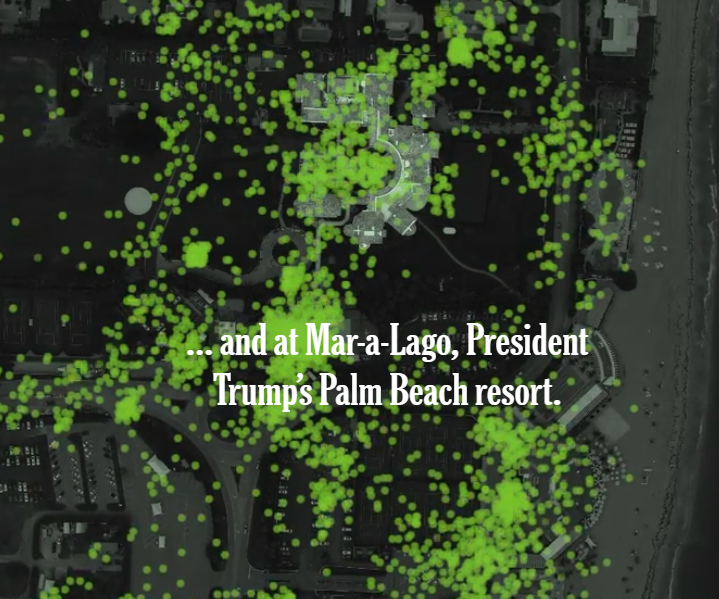

One search turned up more than a dozen people visiting the Playboy Mansion, some overnight. Without much effort we spotted visitors to the estates of Johnny Depp, Tiger Woods and Arnold Schwarzenegger, connecting the devices’ owners to the residences indefinitely.

If you lived in one of the cities the dataset covers and use apps that share your location — anything from weather apps to local news apps to coupon savers — you could be in there, too.

If you could see the full trove, you might never use your phone the same way again.

THE DATA REVIEWED BY TIMES OPINION didn’t come from a telecom or giant tech company, nor did it come from a governmental surveillance operation.

It originated from a location data company, one of dozens quietly collecting precise movements using software slipped onto mobile phone apps. You’ve probably never heard of most of the companies — and yet to anyone who has access to this data, your life is an open book.

They can see the places you go every moment of the day, whom you meet with or spend the night with, where you pray, whether you visit a methadone clinic, a psychiatrist’s office or a massage parlor.

The Times and other news organizations have reported on smartphone tracking in the past. But never with a data set so large.

Even still, this file represents just a small slice of what’s collected and sold every day by the location tracking industry — surveillance so omnipresent in our digital lives that it now seems impossible for anyone to avoid.

It doesn’t take much imagination to conjure the powers such always-on surveillance can provide an authoritarian regime like China’s.

Within America’s own representative democracy, citizens would surely rise up in outrage if the government attempted to mandate that every person above the age of 12 carry a tracking device that revealed their location 24 hours a day.

Yet, in the decade since Apple’s App Store was created, Americans have, app by app, consented to just such a system run by private companies.

Now, as the decade ends, tens of millions of Americans, including many children, find themselves carrying spies in their pockets during the day and leaving them beside their beds at night — even though the corporations that control their data are far less accountable than the government would be.

“The seduction of these consumer products is so powerful that it blinds us to the possibility that there is another way to get the benefits of the technology without the invasion of privacy. But there is,” said William Staples, founding director of the Surveillance Studies Research Center at the University of Kansas. “All the companies collecting this location information act as what I have called Tiny Brothers, using a variety of data sponges to engage in everyday surveillance.”

In this and subsequent articles we’ll reveal what we’ve found and why it has so shaken us. We’ll ask you to consider the national security risks the existence of this kind of data creates and the specter of what such precise, always-on human tracking might mean in the hands of corporations and the government. We’ll also look at legal and ethical justifications that companies rely on to collect our precise locations and the deceptive techniques they use to lull us into sharing it.

Today, it’s perfectly legal to collect and sell all this information.

In the United States, as in most of the world, no federal law limits what has become a vast and lucrative trade in human tracking.

Only internal company policies and the decency of individual employees prevent those with access to the data from, say, stalking an estranged spouse or selling the evening commute of an intelligence officer to a hostile foreign power.

Companies say the data is shared only with vetted partners. As a society, we’re choosing simply to take their word for that, displaying a blithe faith in corporate beneficence that we don’t extend to far less intrusive yet more heavily regulated industries.

Even if these companies are acting with the soundest moral code imaginable, there’s ultimately no foolproof way they can secure the data from falling into the hands of a foreign security service.

Closer to home, on a smaller yet no less troubling scale, there are often few protections to stop an individual analyst with access to such data from tracking an ex-lover or a victim of abuse.

IN MOST CASES, ascertaining a home location and an office location was enough to identify a person. Consider your daily commute: Would any other smartphone travel directly between your house and your office every day?

Describing location data as anonymous is “a completely false claim” that has been debunked in multiple studies, Paul Ohm, a law professor and privacy researcher at the Georgetown University Law Center, told us. “Really precise, longitudinal geolocation information is absolutely impossible to anonymize.”

“D.N.A.,” he added, “is probably the only thing that’s harder to anonymize than precise geolocation information.”

Yet companies continue to claim that the data are anonymous. In marketing materials and at trade conferences, anonymity is a major selling point — key to allaying concerns over such invasive monitoring.

To evaluate the companies’ claims, we turned most of our attention to identifying people in positions of power. With the help of publicly available information, like home addresses, we easily identified and then tracked scores of notables. We followed military officials with security clearances as they drove home at night. We tracked law enforcement officers as they took their kids to school. We watched high-powered lawyers (and their guests) as they traveled from private jets to vacation properties. We did not name any of the people we identified without their permission.

The data set is large enough that it surely points to scandal and crime but our purpose wasn’t to dig up dirt. We wanted to document the risk of underregulated surveillance.

Watching dots move across a map sometimes revealed hints of faltering marriages, evidence of drug addiction, records of visits to psychological facilities.

Connecting a sanitized ping to an actual human in time and place could feel like reading someone else’s diary.

In one case, we identified Mary Millben, a singer based in Virginia who has performed for three presidents, including President Trump. She was invited to the service at the Washington National Cathedral the morning after the president’s inauguration. That’s where we first found her.

She remembers how, surrounded by dignitaries and the first family, she was moved by the music echoing through the recesses of the cathedral while members of both parties joined together in prayer. All the while, the apps on her phone were also monitoring the moment, recording her position and the length of her stay in meticulous detail. For the advertisers who might buy access to the data, the intimate prayer service could well supply some profitable marketing insights.

“To know that you have a list of places I have been, and my phone is connected to that, that’s scary,” Ms. Millben told us. “What’s the business of a company benefiting off of knowing where I am? That seems a little dangerous to me.”

Like many people we identified in the data, Ms. Millben said she was careful about limiting how she shared her location. Yet like many of them, she also couldn’t name the app that might have collected it. Our privacy is only as secure as the least secure app on our device.

“That makes me uncomfortable,” she said. “I’m sure that makes every other person uncomfortable, to know that companies can have free rein to take your data, locations, whatever else they’re using. It is disturbing.”

[Related: What’s the Worst That Could Happen With My Phone Data? — Our journalists answers your questions about their investigation into how companies track smartphone users.]

The inauguration weekend yielded a trove of personal stories and experiences: elite attendees at presidential ceremonies, religious observers at church services, supporters assembling across the National Mall — all surveilled and recorded permanently in rigorous detail.

Protesters were tracked just as rigorously.

After the pings of Trump supporters, basking in victory, vanished from the National Mall on Friday evening, they were replaced hours later by those of participants in the Women’s March, as a crowd of nearly half a million descended on the capital.

Examining just a photo from the event, you might be hard-pressed to tie a face to a name. But in our data, pings at the protest connected to clear trails through the data, documenting the lives of protesters in the months before and after the protest, including where they lived and worked.

We spotted a senior official at the Department of Defense walking through the Women’s March, beginning on the National Mall and moving past the Smithsonian National Museum of American History that afternoon. His wife was also on the mall that day, something we discovered after tracking him to his home in Virginia. Her phone was also beaming out location data, along with the phones of several neighbors.

The official’s data trail also led to a high school, homes of friends, a visit to Joint Base Andrews, workdays spent in the Pentagon and a ceremony at Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall with President Barack Obama in 2017 (nearly a dozen more phones were tracked there, too).

Inauguration Day weekend was marked by other protests — and riots. Hundreds of protesters, some in black hoods and masks, gathered north of the National Mall that Friday, eventually setting fire to a limousine near Franklin Square. The data documented those rioters, too. Filtering the data to that precise time and location led us to the doorsteps of some who were there. Police were present as well, many with faces obscured by riot gear. The data led us to the homes of at least two police officers who had been at the scene.

As revealing as our searches of Washington were, we were relying on just one slice of data, sourced from one company, focused on one city, covering less than one year. Location data companies collect orders of magnitude more information every day than the totality of what Times Opinion received.

Data firms also typically draw on other sources of information that we didn’t use. We lacked the mobile advertising IDs or other identifiers that advertisers often combine with demographic information like home ZIP codes, age, gender, even phone numbers and emails to create detailed audience profiles used in targeted advertising. When datasets are combined, privacy risks can be amplified. Whatever protections existed in the location dataset can crumble with the addition of only one or two other sources.

There are dozens of companies profiting off such data daily across the world — by collecting it directly from smartphones, creating new technology to better capture the data or creating audience profiles for targeted advertising.

The full collection of companies can feel dizzying, as it’s constantly changing and seems impossible to pin down. Many use technical and nuanced language that may be confusing to average smartphone users.

While many of them have been involved in the business of tracking us for years, the companies themselves are unfamiliar to most Americans.

(Companies can work with data derived from GPS sensors, Bluetooth beacons and other sources. Not all companies in the location data business collect, buy, sell or work with granular location data.)

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/1...phone.html

(1)

(1) (0)

(0)