CDiddy, This is not difficult: A trial tries t

Post# of 157708

This is not difficult: A trial tries to determine if a drug works. The way this is done is by testing the hypothesis that it does not work. In lay terms we ask ourselves: what is the possibility that the drug does nor work ?? If it is low we conclude it works. This is the p-value.

Now, let’s use common language: if the p-value is small we likely don’t have a “false positive”, i.e we think the drug works and it doesn’t.

But, you gave a good example. Let’s say we have 4 people in a trial: 2 in drug and 2 in placebo and the two patients in placebo die and 1 in drug die (50% death reduction). Do we conclude that we can commercialize the drug ???

No, because if we do another trial the results might be very well that all four survive or none. And we can’t draw conclusions.

So, we need certain number of patients and “events”. (deaths' or survivals)

Now, in the other side of the spectrum, that if we think that the drug does not work and, in reality, it works ??? This is a “false negative”.

This is the Power of the trial. In may one might say the the false positive is more important that the false negative but this is not always the case. The FDA normally works with 80%-90% for this value. We learned as of late that the HGEN trial is designed to meet 90% power.

I don’t know what is the power designed into our trial, but one can make what is called post-hoc analysis which is simple to take some assumed results and THEN calculate what power it yields.

In doing so I have concluded that we are underpowered, this meaning that if we had a p=0.05 our power would be lower than 90%

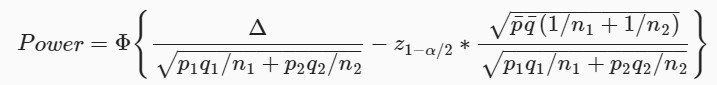

As for how is calculated find below a formula. is not complicated but one needs a good calculator or tables (I am posting just for reference as you asked how is calculated, please PM if need more info.):

However, the lesson here is that if the number of "events" reduces the power suffers as a consequence, the more patients and "events" the better (higher) this number is.

(7)

(7) (0)

(0)