Central American Countries Are Helping Middle East

Post# of 65629

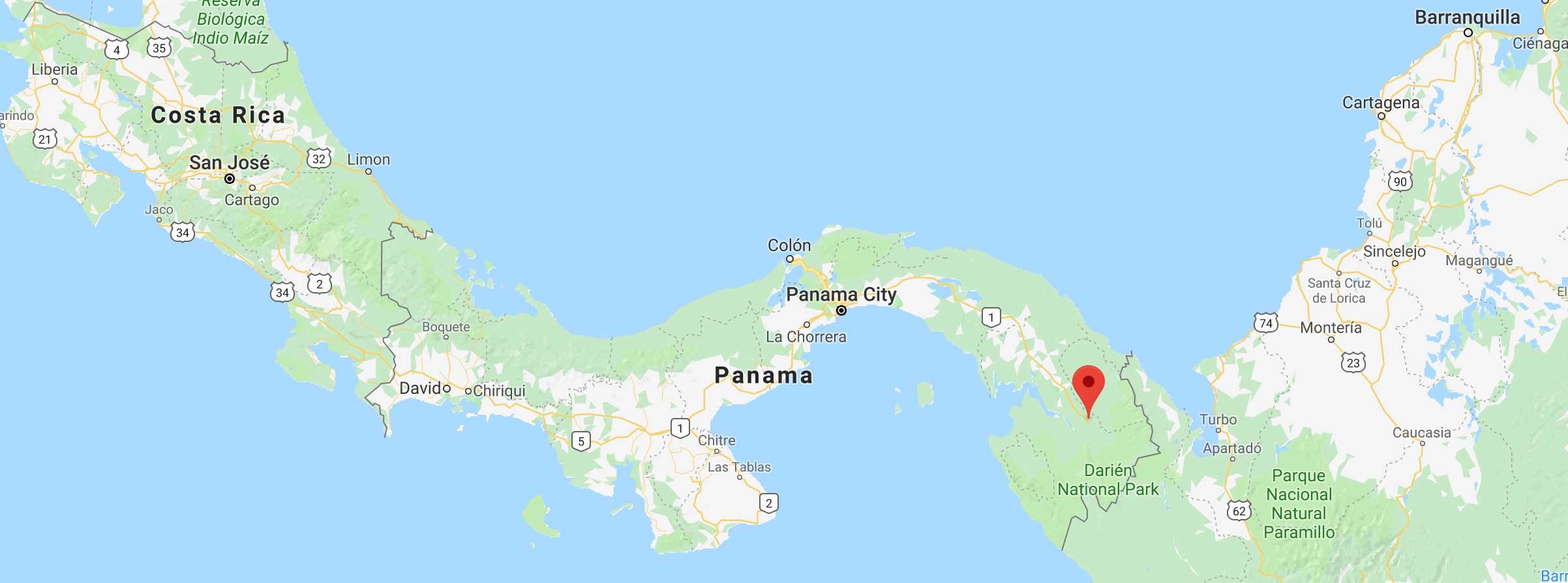

Panama and Costa Rica are chokepoints on the migrant trail followed by people from other continents seeking easier U.S. entry through our porous border with Mexico.

January 2, 2019

In December 2018, the Center for Immigration Studies dispatched Senior National Security Fellow Todd Bensman to Panama and Costa Rica to investigate President Donald Trump’s widely ridiculed assertions that suspected terrorists had been apprehended among Middle East migrants through Latin America.

Panama is a geographic chokepoint, or bottleneck, through which migrants from countries of the Middle East, who are moving out of South America, must push on their way to the U.S. border.

The following article is based on Bensman’s on-the-ground research over two weeks. His video reports, photos, and writings from the trip can be found here .

Golfito, Costa Rica — It was here in March 2017, at the main aluminum structure of a government migrant camp, that federal Costa Rican police arrested Ibrahim Qoordheen of Somalia as a suspected al Shabaab terrorist operative on his way to the U.S. southern border.

Qoordheen had been smuggled from Zambia to Brazil, passed through Panama, and was making his way north through Costa Rica when the Americans had him arrested here, 20 miles inside Costa Rica, according to an American intelligence official with knowledge of the case who spoke on condition of anonymity. The Golfito camp, with a capacity of 250, was set up as a two-day rest station for South America-exiting migrants whom the governments of Panama and Costa Rica register and help move through northward to Nicaragua.

Golfito migrant camp, Costa Rica where Ibrahim Quoordheen was arrested in 2017. Photos by Todd Bensman.

Golfito migrant camp, Costa Rica.

Luckily, the Somali stayed long enough for an American intelligence analyst working with the name he had provided in Panama to unscramble it and match it to a pre-existing intelligence file that identified him as intertwined with an al Shabaab cell and smuggling network in Zambia, the U.S. intelligence official said.

The Americans interviewed Qoordheen at length, but the Somali gave up nothing, the U.S. officer said. The Americans then arranged to have him deported to Zambia, the officer said. It turns out the Qoordheen case was only one of other such episodes about which the American public was never told, where terrorist suspects were discovered migrating through Latin America to the U.S. border.

Terrrorists Know the U.S. Border Is Not Secure

A Costa Rican immigration service official whose jurisdiction includes the Golfito camp disclosed that at least several other U.S.-bound suspected terrorists also were pulled from this camp since Qoordheen’s March 2017 arrest, likewise based on significant derogatory U.S. counterterrorism intelligence. The Costa Rican official declined to provide specifics of the intelligence beyond that it involved terrorism, offering only that: “Most are good, but some are bad.”

The American public was never told that Qoordheen and other suspected terrorists were pulled off U.S.-bound migrant routes in distant Costa Rica and Panama because such information is usually classified or not disclosable, in line with standard practice to protect ongoing investigations and operations .

That necessary opacity, unfortunately, seems to have given life to denialism about President Trump’s claims that terrorists are among migrants from countries of terror concern, like the Middle East. The skeptics have demanded proof then cited Trump perfidy when protected intelligence wasn’t provided. Trump’s assertions were thus ridiculed and dismissed as unsupported fear-mongering.

But the rejectionists, many of whom obviously do not know that a central homeland security practice is threat preemption, are wrong. Down here, on the southern-most leg of migrant routes to the American border, it is they who invite ridicule and eye rolls.

American, Panamanian, and Costa Rican law enforcement and intelligence officials are engaged in actual programs here to hunt, investigate, and deport real terrorist suspects who are, in fact, discovered among the thousands of migrants from the Middle East, Horn of Africa, and South Asia funneling through this section of Latin America—as President Trump said and as I saw and heard on the ground.

Migrants from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka processing through Costa Ricans customs at Paso Canoas on the Panama border.

They are working at it here because sheer geography pushes tens of thousands of U.S.-bound migrants from all over the world who pass from South America landing zones through these two countries as they push north. Panama and Costa Rica are chokepoints on the migrant trail where “extra-continental” travelers, as they are sometimes called at the American embassies, can become known in the greatest concentrations.

Terror Migrants Pulled From U.S. Border Routes

Some acknowledgments of terror travel through these countries—and of the American efforts to mitigate it—are in public evidence, even if the underlying reporting remains confidential.

A December 19 Immigration and Customs Enforcement statement, for instance, announced the deportation of U.S.-convicted Brazil-based smuggler Sharafat Ali Khan after time served for transporting at least 100 aliens from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh through South and Central America to the United States. The statement offered this nugget, with the usual lack of elaboration: “Several of the individuals smuggled by Khan’s organization had suspected ties to terrorist organizations.”

The new statement seems to comport with earlier reporting by The Washington Times that one of these individuals was an Afghan involved in a plot to attack in the United States or Canada and had family ties to members of the Taliban.

Also in December 2018, an INTERPOL statement announcing the arrests of 49 human smugglers in the multi-nation “Operation Andes,” networks that funneled migrants from places like the Middle East into Panama and out of Costa Rica en route to the U.S. border, said four arrestees were linked to fraud, homicide, “and terrorism.”

Clearly, even if we can’t know all the details, something has been happening in this part of the world involving migrants who show up in terrorism intelligence reporting databases.

Dozens of migrants suspected of terrorism involvements are also reaching the U.S. border. As reported for CIS in a paper titled “Have Terrorists Crossed?”

i ntelligence community sources said more than 100 migrants caught at the American southern border, or caught en route, were on U.S. terror watch lists between 2012 and 2017. More than half were first noticed at the American border; many of the rest were caught en route, like Qoordheen.

Fifteen terrorists are listed and described in the CIS report, including a Somali migrant who passed unnoticed through Panama in 2011, crossed the Mexico-California border, and went on to commit two 2017 vehicle ramming attacks in Alberta, Canada while carrying an ISIS flag.

Governments Assist in Human Smuggling

The terrorist travel threat associated with migration through this area (from the Middle East, Horn of Africa, and South Asia) is regarded as a primary American law enforcement and intelligence preoccupation in Panama, intelligence officials say. The U.S. effort is purposefully centered on the migration through Panama and Costa Rica because homeland security professionals, some of whom agreed to talk anonymously, regard the migration danger as real, present, and

One reason migration from countries of terror concern is visible here is that Panama and Costa Rica follow a catch, rest, and release policy, virtually unknown to the American public, locally called “Controlled Flow.”

The 2016 policy has Panama’s military collecting special interest migrants hiking in from Colombia’s wilderness borderlands.

These migrants number about 700 per week these days, according to one Panamanian military official.

The military’s Central Battallion’s Oriental Brigade based in Yaviza, the last town on Panama’s Highway 1, places them in camps where they are fed and medically treated. The military then provides them with temporary legal status and commercially buses them north to the Costa Ricans, who likewise provide the means and resources for the migrants to pass north again on through to Nicaragua, where smugglers often take things in hand again.

(See video report about Controlled Flow here). https://www.cis.org/Bensman/Panama-and-Costa-...low-Policy

“There is a thing the world does not see, and it is the work we do,” said a ranking Panamanian military commander who spoke on condition of anonymity. “No other country, or, I believe, any country in all of Latin America, does what Panama does. And that is to receive [foreign citizens], to aid them, give them medication and to organize them” for transport to Costa Rica. Asked if terrorists may be placed on this human conveyer belt, the officer offered, with a knowing chuckle, “Maybe!”

The Panamanian central government declined repeated interview requests and decided not to reply to a list of CIS questions about its this policy, saying only that “We can assure you that Panama and the U.S. are strong partners in ensuring we have secure migration flows and inpromoting regional security.”

Several Panamanian national Assembly members explained how the policy works in the interests of both Panama and most of the migrants. For Panama, they said, the policy removes the cost burdens of interdicting, detaining, processing legal asylum claims, and deportation. It also protects migrants from smugglers while exploiting what most want: to reach America.

“Panama is like a bridge or a passway to another country,” said Juan Carlos Arrango, of the ruling coalition Panamanian Popular Party. “

Wherever they come from, by boat, plane, or walking through the Darien jungle, they’re very vocal in saying, ‘We don’t want to stay in Panama. We want to pass through, to the north.” So, Arrango said, the government is happy to see to that.

Middle East Migrants and Terrorist Suspects in Panama

American law enforcement has taken some advantage of controlled flow to filter the migrants for terrorism history or connections, even though unknown numbers of migrants choose illicit smuggling through the region instead.

American officials declined requests to discuss these efforts on the record. Others, however, did speak anonymously.

Panama and Costa Rica follow a catch, rest, and release policy.

“This is national security,” the American officer said of the programs filtering terrorists from the migrant flows through in Panama. “We’ve extended our border.”

The publicly available annual U.S. State Department Country Reports on Terrorism, released most recently in September 2018, provided one confirming peek at the American counterterrorism partnership with Panama.

It said one program objective there now was “to detain and repatriate individuals for whom there were elevated suspicions of links to terrorism.”

This is significant because it means America has intercepted terror suspects flown to their home countries from Panama, as was done with Qoordheen, rather than to gamble with a U.S. border entry and an attack on the homeland.

An illustrative August 2016 case involved six Pakistanis who entered Panama from Colombia on their way to the American border and were pulled off the route then deported home.

The deportations of the six were publicly reported but not the reasons why, so it attracted almost no notice. But Juan Carlos, political editor for La Prensa newspaper in Panama City, said his paper was told the Pakistanis were arrested on suspicions that they were associated with al Qaeda and after they were seen taking photos of sensitive sites around the city, including the Panama Canal.

“The government closed out all information about that news,” the journalist said, adding that this wasn’t the only such case. “Other (terrorism suspect) cases were shut down too. So officially, we have no news to report.”

Terror List Hits Trigger ‘Deep Dive’ Investigations

The American intelligence officer quoted earlier in this report also described processes that launch in Panama when migrants hit on terror watch list databases or otherwise come to U.S. attention.

Such hits are fairly common, and when they occur, trigger in-country “deep dive,” investigations and analyses that might involve foreign intelligence services and agencies, as well as interviews with the suspected migrants, the U.S. official said.

Of course, there’s no publicly reportable metric for something that doesn’t go boom.

Some of these investigations clear things up pretty quickly with no terrorism finding, or maybe just a distant association to someone that wouldn’t warrant deportation. But enough other cases surface that warrant hard effort, vigilance, and deportations from Panama that reduce terror attack risks the American public would never know about.

For example, the deep dive process had to be applied to one Pakistani pulled off the route in Panama when he was found to have a long history with a terrorist organization, the American security official said.

The Pakistani remained in Panamanian custody, at the behest of the Americans, for about a full year during the investigation. The investigation turned up no specific terrorism plot, but because of his confirmed history as a terrorist, the Pakistani was deported by plane anyway to reduce risk, the officer said.

The Costa Rica immigration official also cited earlier in this report explained that American counterterrorism officers in the region pay close attention to the migrant traffic coming through the camp in Golfito and maintain “close contact” about the Costa Rica services.

The Americans, the Costa Rican official said, are mainly interested in interviews of migrants from Iraq, Iran, Syria, Pakistan, and countries like those, because of the elevated chance those migrants are terrorists.

The Americans sometimes call the Golfito migrant camp and have immigration officers interview such migrants—in an interview room I saw—and ask that the intelligence reports be forwarded to the U.S. embassy where the Americans work. That’s how other suspected terrorists were caught here, the Costa Rican official said.

“It’s important if they suspect there is a person traveling to the U.S. for terrorism, they need to know where they are staying and to know who they are,” the Costa Rican official said.

The author with Costa Rica’s Policia de Frontera border guard.

One way migrants with terrorism intelligence records are getting noticed is through another major American-backed counterterrorism program here known by the shorthand “BitMap.”

Americans supplied equipment and trained the Panamanians and Costa Ricans to collect retinal eye scans, fingerprints and facial photography of migrants moving through the countries, the State Department country reports on terrorism document said.

I watched as U.S.-trained Costa Rican immigration officials collected biometrics on Iranians, Pakistanis, Eritreans, and Iraqis. This allows homeland security to run the information against international terrorism databases where perhaps the migrant’s biometrics had been enterered somewhere else previously.

An African migrant in Costa Rica submits to providing fingerprints that will end up in American databases. Costa Rican immigration officers were trained to administer the collections, 12/18.

None of this, of course, is communicated to the American public, for reasons of operational security that enable skeptics to mock the dearth of “evidence.” And, of course, there’s no publicly reportable metric for something that doesn’t go boom.

Foreigners Pour Through the Darien Gap

Let no one ever again say that migrants from countries of terror concern, to include the Middle East, aren’t moving in significant numbers through Latin America to the U.S. border, or that the risk of terrorists or those predisposed toward terrorism would mix with this traffic. American homeland security certainly believes so, due in no small part to the discovery of terrorist suspects in this flow.

In both Panama and Costa Rica, I observed hundreds of mostly young male migrants from countries of terrorism concern, of often unverifiable identity and backgrounds, traveling toward the U.S. border.

I photographed and spoke to them. Some told me they were from Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Eritrea. I interviewed an Iranian, an Iraqi, a Pakistani, and a Bangladeshi. Some of their interviews are posted here for all to see.

https://www.cis.org/Immigration-Topic/CIS-Inv...Costa-Rica

At issue is that American authorities don’t know who many of them are and can’t verify their stories.

All of those I interviewed said they had no identification with them. At the main bus station in Panama, one day, I met two travelers who initially identified themselves to me as Indonesian, a nation riven with violent Islamist groups, then rushed away from me when I identified myself as an American.

Thousands like them are on the move through here, heading for the southern border every year, where they will show up as complete strangers.

Todd Bensman is a Texas-based senior national security fellow for the Center for Immigration Studies and a writing fellow for the Middle East Forum. For nearly a decade, Bensman led counterterrorism-related intelligence efforts for the Texas Intelligence and Counterterrorism Division.

Follow him on Twitter @BensmanTodd. Bensman also worked for The Dallas Morning News, CBS, and Hearst Newspapers. He reported extensively on national security and border issues after 9/11 and worked from more than 25 countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.

http://thefederalist.com/2019/01/02/central-a...u5w.mailto

(1)

(1) (0)

(0)