Covering soil in plastic has been a boon for agric

Post# of 52098

1. Why is plastic mulch a problem?

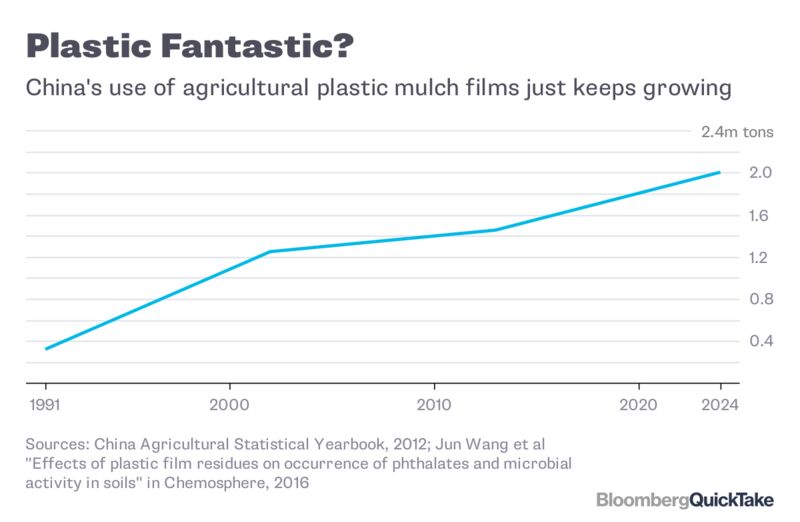

The plastic isn’t biodegradable and scientists predict it could persist in soil for centuries. It’s a worldwide issue, but one that’s especially acute for China, where about a fifth of arable land contained levels of toxins exceeding national standards, according to 2014 government estimates. Further, the film used in China is less than 0.008 millimeters thick — about half that of sheets used in the U.S., Europe and Japan. That thinness makes the material less robust and more difficult to recover after use. China is predicted to increase its use of plastic mulch by 38 percent to more than 2 million metric tons a year by 2024.

2. What harm does plastic mulch do?

Heaps. Over time, film residue can decrease soil porosity and air circulation, change microbial communities, and potentially lower farmland fertility, scientists have found. Fragments of plastic film have also been shown to release potentially carcinogenic phthalate acid esters into the soil, where they can be taken up in vegetables and pose a human health risk when the food is consumed.

3. Is that all?

There’s more. Film fragments left in fields can also accumulate pesticides and other toxins applied to crops. This is a special risk for sheep, goats and other livestock grazing on crop stalks because of their potential to ingest plastic material or the chemicals that leach from it. When cotton crops are grown in plastic-contaminated soil, the lint risks being contaminated and the quality downgraded because traces of plastic can interfere with the coloring process. And then there’s the plastic pollution that makes its way into rivers and oceans, which can be toxic for aquatic life.

4. Can the plastic be recycled?

It takes about 16 hours to remove polyethylene sheets from 1 hectare (2.5 acres) of farmland in a process that requires manual labor, even when machinery is used. It’s such a time-consuming and costly process that plastic often is left in the soil after harvesting, risking its breakup into pieces when land is prepared for the next crop. The pieces that are collected are often contaminated with too much dirt and debris to be recycled directly from the field, so they are usually discarded in a dump or burned, emitting toxic substances.

5. What is the government doing about it?

The Ministry of Agriculture published an action plan in May that requires farmers to recycle plastic film and use sheets that are at least 0.01 millimeters thick. Meantime, the National People’s Congress, the country’s top legislative body, is seeking public comment on a draft of the country’s first national soil-pollution control law which includes stiff penalties for offenders. By the end of 2018, the government aims to complete a detailed nationwide survey on farmland pollution that will identify heavily contaminated areas; they will be prohibited from growing crops.

6. What other options are there?

While the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and other groups are exploring ways to address the residue problem, solutions face technical and economic challenges. Alternatives to polypropylene include biodegradable polymers, or mixtures with biodegradable synthetic materials, such as polypropylene carbonate, and polyethylene-based oxo-degradable polymers to which additives are incorporated to accelerate degradation. Bast-fiber mulching film, made from tree bark, is another option that’s been shown to have good thermal insulation and moisture retention, but is expensive and loses its strength when wet. More recently, non-contaminating liquid membranes have emerged as an alternative. The approach involves bonding soil particles together to form a black solidified film after mixing with water and spraying onto the soil surface. The downside is cost. Biodegradable polymer film is about 1,350 yuan ($206) per hectare more expensive than polyethylene film. Scientists in Spain may have an another answer: wax worms. Larvae of the wax moth Galleria mellonella are able to biodegrade polyethylene, researchers at the Institute of Biomedicine and Biotechnology of Cantabria showed in a study published in April.

7. What will happen if nothing is done?

The more polluted China’s farmland becomes, the more difficult feeding its 1.4 billion citizens becomes. It takes about 1 acre to feed the average U.S. consumer. China only has about 0.2 acres of arable land per citizen, including fields degraded by pollution and contaminants. Government studies in 2014 found that some vegetable plots were dosed with high levels of heavy metals such as cadmium, just one of a series of poison scares that has made the public wary of domestically produced food. China is increasing its grain imports, even though the government has targeted self-sufficiency in staples, such as wheat.

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)