Dead End Drinks The Rise and Fall of Three Icon

Post# of 128990

Quote:

Dead End Drinks

The Rise and Fall of Three Iconic Failures

http://www.drunkard.com/55-dead-end-drinks/

Quote:

The winos of the day generally preferred Gallo’s more high-powered offerings: Night Train and Thunderbird. Ripple found much more acceptance with the younger set; it became the drink of choice for college kids (and their younger siblings) and made headway in the black community as well.

Ripple’s pop culture impact was considerable. Fred Sanford (Redd Foxx) of the popular sitcom Sandford and Son led the charge, declaring his beverage of choice “the national drink of Watts.” Fred improvised all sorts of splendid Ripple cocktails, including Mintchipple (mint julep and Ripple), Cripple (cream and Ripple), Champipple (Champagne and Ripple) and Manischipple (Manischewitz and Ripple).

Ripple

The Lost Dauphin of Pop Wines

1960-1984 E&J Gallo Winery

The Name: Some armchair etymologists claim “ripple” was ‘30s bluesman slang for a type of cocktail, but if that were true it would surely have popped up in at least one old blues song, cocktail manual or slang dictionary, which it didn’t. More likely it just seemed like a nice name for a new kind of drink. Ripple is a pleasant word describing, as it does, liquid making a pretty motion.

The Concept: Ripple came to life as a wine maker’s attempt to seize a chunk of the youth market. Something light and fizzy that might appeal to novice drinkers who didn’t particularly care for the taste of hops, or alcohol for that matter. Early TV and radio spots called it a “new drink for lively people,” “the ice cold refresher with twice the pleasure,” and, a bit oddly, “the wine that winks back at you.” The glass of the bottle bore a distinctive ripple pattern but, tellingly, no mention of the E&J Gallo Winery. Following the booming success of the original Red flavor, Pear and Pagan Pink were introduced in the mid-60s.

The Rise: Gallo’s timing, it turned out, was better than they could have imagined. A new generation of drinkers was rising up, and these kids, who the media termed “hippies,” were keenly interested in rebelling against everything their parents stood for, including their choice of adult refreshment. And here was something new and different, even rebellious. The wine snobs said it wasn’t really wine and the grown-ups dismissed it as spiked punch in a bottle.

History has unjustly vilified Ripple as a wino wine. Social workers and other assorted handwringers of the day attached so much infamy to its name that one imagines it was some manner of vile high-proof elixir reeking of brimstone. In fact, Ripple was merely an artificially-flavored, lightly-carbonated sweet wine drink weighing in at 11%. It was a wine cooler (before they called it that) with a bit of a bite.

The winos of the day generally preferred Gallo’s more high-powered offerings: Night Train and Thunderbird. Ripple found much more acceptance with the younger set; it became the drink of choice for college kids (and their younger siblings) and made headway in the black community as well.

Ripple’s pop culture impact was considerable. Fred Sanford (Redd Foxx) of the popular sitcom Sandford and Son led the charge, declaring his beverage of choice “the national drink of Watts.” Fred improvised all sorts of splendid Ripple cocktails, including Mintchipple (mint julep and Ripple), Cripple (cream and Ripple), Champipple (Champagne and Ripple) and Manischipple (Manischewitz and Ripple).

Ripple was also immortalized in song: blues artist Dan Shoemake sang its praises, as did Arlo Guthrie, Gordon Lightfoot, Johnnie Johnson, Loudon Wainwright III, Hanoi Rocks, Motorhead and Easy-E.

The Fall: Why Gallo ceased production of Ripple in the mid-’80s is something of a mystery. The winery never bothered to explain, which isn’t surprising when you remember they refrained from putting their name on the bottle.

Some alcohol historians (hoochstorians, if you will) claim Ripple was ruthlessly purged in an attempt by Gallo to clean up its image. While it’s true that the winery was fancying up its product line (in 1974 they even went so far as to start selling wine with actual corks), the theory doesn’t ring true. If Gallo was really interested in polishing its name they would have put to bed the much more notorious Night Train and Thunderbird, both of which are produced to this day.

No, it was a shrinking market share that did Ripple in. The niche Ripple had seized was being squeezed on all sides by its Gallo siblings: the kids were turning to the sweeter and lighter Boone’s Farm and the aging hippies were graduating to Gallo’s cheap jug wines. Furthermore, Gallo wanted to make room for their new innocuous brand of wine coolers, Bartles & Jaymes, which rolled out the same year Ripple vanished. Ripple was the Gatsby of its day, a shady relative who was tolerated so long as he was raking in the dough, then promptly cast out when he fell on hard times.

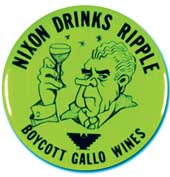

Availability: Surviving bottles are extremely rare, to the degree that one optimistic gent attempted to sell an unopened bottle of Red Ripple for $5000 on Ebay. He didn’t get any takers, but Ripple can still boast an Nixon Drinks Rippleimpressive appreciation in value: unopened bottles (originally going for a buck) generally sell in the $150-$200 range.

Trivia: During their long and bitter boycott of Gallo, the United Farm Workers released buttons claiming “Nixon Drinks Ripple.” Which probably wasn’t true.

Happy Birthday!

(1)

(1) (0)

(0)