Hey Mexicali horseshit (and heifer shit): We gave

Post# of 65629

We gave you 1/2 your country back

after you tried to slaughter some of us.

Remember the Alamo.

We even gave you back Mexico City.

And the countryside and towns north of that.

oops

So go piss up a rope 'hombre panocha'.

The Mexican–American War, also known as the Mexican War, the U.S.–Mexican War, the U.S.–Mexico War or the Invasion of Mexico[dubious – discuss] (Spanish: Intervención estadounidense en México, Guerra de Estados Unidos-México), was an armed conflict between the United States of America and the United Mexican States from 1846 to 1848. It followed in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory in spite of its de facto secession in the 1836 Texas Revolution.

After its independence in 1821 and brief experiment with monarchy, Mexico became a republic in 1824. It was characterized by considerable instability, leaving it ill-prepared for conflict when war broke out in 1846.[7] Native American raids in Mexico's sparsely settled north in the decades preceding the war prompted the Mexican government to sponsor migration from the U.S. to the Mexican province of Texas to create a buffer. However, Texans from both countries revolted against the Mexican government in the 1836 Texas Revolution, creating a republic not recognized by Mexico, which still claimed it as part of its national territory. In 1845, Texas agreed to an offer of annexation by the U.S. Congress, and became the 28th state on December 29 that year.[8]

In 1845, James Polk, the newly-elected U.S. president, made a proposition to the Mexican government to purchase the disputed lands between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. When that offer was rejected, American forces commanded by Major General Zachary Taylor were moved into the disputed territory. They were then attacked by Mexican forces, who killed 12 U.S. soldiers and took 52 as prisoners. These same Mexican troops later laid siege to an American fort along the Rio Grande.[9] This led to the war and the eventual loss of much of Mexico's northern territory.

U.S. forces quickly occupied Santa Fe de Nuevo México and Alta California Territory, and then invaded parts of Central Mexico (modern-day Northeastern Mexico and Northwest Mexico); meanwhile, the Pacific Squadron conducted a blockade, and took control of several garrisons on the Pacific coast farther south in Baja California Territory. The U.S. army, under the command of Major General Winfield Scott, captured the capital, Mexico City, marching from the port of Veracruz.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war and specified its major consequence: the Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México to the United States. The U.S. agreed to pay $15 million compensation for the physical damage of the war. In addition, the United States assumed $3.25 million of debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico acknowledged the loss of Texas and thereafter cited the Rio Grande as its national border with the United States.

The territorial expansion of the United States toward the Pacific coast had been the goal of US President James K. Polk, the leader of the Democratic Party.[10] At first, the war was highly controversial in the United States, with the Whig Party, anti-imperialists, and anti-slavery elements strongly opposed. Critics in the United States pointed to the heavy casualties suffered by U.S. forces and the conflict's high monetary cost. The war intensified the debate over slavery in the United States, contributing to bitter debates that culminated in the American Civil War.

In Mexico, the war came in the middle of political turmoil, which increased into chaos during the conflict. The military defeat and loss of territory was a disastrous blow, causing Mexico to enter "a period of self-examination ... as its leaders sought to identify and address the reasons that had led to such a debacle."[11] In the immediate aftermath of the war, some prominent Mexicans wrote that the war had resulted in "the state of degradation and ruin" in Mexico, further claiming, for "the true origin of the war, it is sufficient to say that the insatiable ambition of the United States, favored by our weakness, caused it."[12] The shift in the Mexico-U.S. border left many Mexican citizens separated from their national government. For the indigenous peoples who had never accepted Mexican rule, the change in border meant conflicts with a new outside power.

Roots of the conflict in Northern Mexico

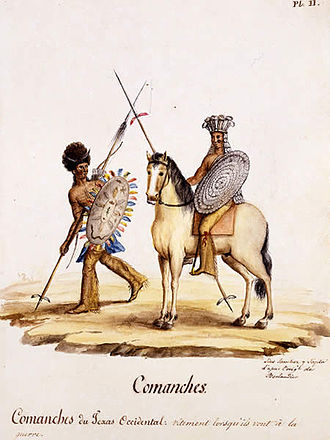

he northern area of Mexico was sparsely settled and not well controlled politically by the government based in Mexico City. After independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico contended with internal struggles that sometimes verged on civil war and the northern frontier was not a high priority. In the sparsely settled interior of northern Mexico, the end of Spanish rule was marked by the end of financing for presidios and for subsidies to indigenous Americans to maintain the peace. There were conflicts between indigenous people in the northern region as well. The Comanche were particularly successful in expanding their territory in the Comanche–Mexico Wars and garnering resources. The Apache–Mexico Wars also made Mexico's north a violent place, with no effective political control.

The Apache raids left thousands of people dead through out northern Mexico. When the United States Army entered northern Mexico in 1846 they found demoralized Mexican settlers. There was little resistance to US forces from the civilian population.[13]

Hostile activity from indigenous people also made communications and trade between the interior of Mexico and provinces such as Alta California and New Mexico difficult. As a result, New Mexico was dependent on the overland Santa Fe Trail trade with the United States at the outbreak of the Mexican–American War.[14]

Mexico's military and diplomatic capabilities declined after it attained independence and left the northern half of the country vulnerable to the Comanche, Apache, and Navajo. The indigenous people, especially the Comanche, took advantage of the weakness of the Mexican state to undertake large-scale raids hundreds of miles into the country to acquire livestock for their own use and to supply an expanding market in Texas and the US.[15]

The Mexican government's policy of settlement of US citizens in its province of Tejas was aimed at expanding control into Comanche lands, the Comancheria. Instead of settlement occurring in the central and west of the province, people settled in East Texas, where there was rich farmland and which was contiguous to southern US slave states. As settlers poured in from the US, the Mexican government took steps to discourage further settlement, including its 1829 abolition of slavery.

In 1836 Mexico was relatively united in refusing to recognize the independence of Texas. Mexico threatened war with the United States if it annexed the Republic of Texas.[16] Meanwhile, U.S. President Polk's assertion of Manifest Destiny was focusing United States interest on westward expansion beyond its existing national borders.

Designs on California

During the Spanish colonial era, the Californias (i.e., the Baja California peninsula and Alta California) were sparsely settled. After Mexico became independent, it shut down the missions and reduced its military presence.

In 1842, the US minister in Mexico, Waddy Thompson, Jr., suggested Mexico might be willing to cede Alta California to settle debts, saying: "As to Texas, I regard it as of very little value compared with California, the richest, the most beautiful, and the healthiest country in the world ... with the acquisition of Upper California we should have the same ascendency on the Pacific ... France and England both have had their eyes upon it."

US President John Tyler's administration suggested a tripartite pact that would settle the Oregon boundary dispute and provide for the cession of the port of San Francisco from Mexico; Lord Aberdeen declined to participate but said Britain had no objection to U.S. territorial acquisition there.[17]

The British minister in Mexico, Richard Pakenham, wrote in 1841 to Lord Palmerston urging "to establish an English population in the magnificent Territory of Upper California", saying that "no part of the World offering greater natural advantages for the establishment of an English colony ... by all means desirable ... that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power but England ... daring and adventurous speculators in the United States have already turned their thoughts in this direction." But by the time the letter reached London, Sir Robert Peel's Tory government, with its Little England policy, had come to power and rejected the proposal as expensive and a potential source of conflict.[18][19]

A significant number of influential Californios were in favor of annexation, either by the United States or by the United Kingdom. Pío de Jesús Pico IV, the last governor of Alta California, was in favor of British annexation.[20]

In 1800, the colonial province of Texas was sparsely populated, with only about 7,000 non-Indian settlers.[21] The Spanish crown developed a policy of colonization to more effectively control the territory. After independence, the Mexican government implemented the policy, granting Moses Austin, a banker from Missouri, a large tract of land in Texas. Austin died before he could bring his plan of recruiting American settlers for the land to fruition, but his son, Stephen F. Austin, brought over 300 American families into Texas.[22] This started the steady trend of migration from the United States into the Texas frontier. Austin's colony was the most successful of several colonies authorized by the Mexican government. The Mexican government intended the new settlers to act as a buffer between the Tejano residents and the Comanches, but the non-Hispanic colonists tended to settle where there was decent farmland and trade connections with American Louisiana, which the United States had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, rather than further west where they would have been an effective buffer against the Indians.

In 1829, as a result of the large influx of American immigrants, the non-Hispanic outnumbered native Spanish speakers in the Texas territory. President Vicente Guerrero, a hero of Mexican independence, moved to gain more control over Texas and its influx of southern non-Hispanic colonists and discourage further immigration by abolishing slavery in Mexico.[21][23] The Mexican government also decided to reinstate the property tax and increase tariffs on shipped American goods. The settlers and many Mexican businessmen in the region rejected the demands, which led to Mexico closing Texas to additional immigration, which continued from the United States into Texas illegally.

In 1834, General Antonio López de Santa Anna became the centralist dictator of Mexico, abandoning the federal system. He decided to quash the semi-independence of Texas, having succeeded in doing so in Coahuila (in 1824, Mexico had merged Texas and Coahuila into the enormous state of Coahuila y Tejas). Finally, Stephen F. Austin called Texians to arms; they declared independence from Mexico in 1836, and after Santa Anna defeated the Texians at the Alamo, he was defeated by the Texian Army commanded by General Sam Houston and captured at the Battle of San Jacinto and signed a treaty recognizing Texas' independence.[8]

Texas consolidated its status as an independent republic and received official recognition from Britain, France, and the United States, which all advised Mexico not to try to reconquer the new nation. Most Texians wanted to join the United States of America, but annexation of Texas was contentious in the US Congress, where Whigs were largely opposed. In 1845 Texas agreed to the offer of annexation by the US Congress. Texas became the 28th state on December 29, 1845.[8]

Origins of the war

The border of Texas as an independent state was originally never settled. The Republic of Texas claimed land up to the Rio Grande based on the Treaties of Velasco, but Mexico refused to accept these as valid, claiming that the Rio Grande in the treaty was the Nueces, and referred to the Rio Grande as the Rio Bravo. The ill-fated Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 attempted to realize the claim to New Mexican territory East of the Rio Grande, but its members were captured and imprisoned.

Reference to the Rio Grande boundary of Texas was omitted from the US Congress's annexation resolution to help secure passage after the annexation treaty failed in the Senate. President Polk claimed the Rio Grande boundary, and when Mexico sent forces over the Rio Grande, this provoked a dispute.[24]

In July 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to Texas, and by October 3,500 Americans were on the Nueces River, ready to take by force the disputed land. Polk wanted to protect the border and also coveted for the U.S. the continent clear to the Pacific Ocean. At the same time Polk wrote to the American consul in the Mexican territory of Alta California, disclaiming American ambitions in California, but offering to support independence from Mexico or voluntary accession to the United States, and warning that the United States would oppose a British or French takeover.[24]

To end another war scare with the United Kingdom over the Oregon Country, Polk signed the Oregon Treaty dividing the territory, angering northern Democrats who felt he was prioritizing Southern expansion over Northern expansion.

In the Winter of 1845–46, the federally commissioned explorer John C. Frémont and a group of armed men appeared in Alta California. After telling the Mexican governor and the American Consul Larkin he was merely buying supplies on the way to Oregon, he instead went to the populated area of California and visited Santa Cruz and the Salinas Valley, explaining he had been looking for a seaside home for his mother.[25] Mexican authorities became alarmed and ordered him to leave. Frémont responded by building a fort on Gavilan Peak and raising the American flag. Larkin sent word that Frémont's actions were counterproductive. Frémont left California in March but returned to California and took control of the California Battalion following the outbreak of the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma.[26]

In November, 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with an offer to the Mexican government of $25 million for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico's provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. US expansionists wanted California to thwart British ambitions in the area and to gain a port on the Pacific Ocean. Polk authorized Slidell to forgive the $3 million owed to US citizens for damages caused by the Mexican War of Independence and pay another $25 to $30 million in exchange for the two territories.[27][28]

Mexico was not inclined nor able to negotiate. In 1846 alone, the presidency changed hands four times, the war ministry six times, and the finance ministry sixteen times.[29] Mexican public opinion and all political factions agreed that selling the territories to the United States would tarnish the national honor.[30] Mexicans who opposed direct conflict with the United States, including President José Joaquín de Herrera, were viewed as traitors.[31] Military opponents of de Herrera, supported by populist newspapers, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico City an insult. When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and deposed. After a more nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga came to power, it publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to Texas;[31] Slidell, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised", returned to the US.[32]

The Mexican Army emerged from the war of independence (1810–1821) as a weak and divided force. Before the war with the United States, the military faced both internal and foreign challenges. The Spanish still occupied the coastal fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and Spain did not recognize Mexico's independence, so that the new nation was at risk for invasion. In 1829, the Spanish attempted to reconquer their former colony and Antonio López de Santa Anna became a national hero defending the homeland.[33] The army had a set of privileges (fueros), established in the colonial era, that gave it jurisdiction over many aspects of its affairs. In general, the military supported conservative positions, advocating a strong central government and upholding privileges of the military and the Catholic Church.

Some military men exercised power in local areas as caudillos and resisted central command. Liberal politicians, such as Valentín Gómez Farías, sought to rein in the military's power. The military faced insurrections and separatist movements in Tabasco, Yucatán, and Texas. The French blockaded in Veracruz in 1838 to collect debts, a conflict known to history as the Pastry War. Compounding the demands on the Mexican military, there were continuing Indian challenges to power in the northern region.[34]

On the Mexican side, only 7 of the 19 states that formed the Mexican federation sent soldiers, armament, and money for the war effort, as the young Republic had not yet developed a sense of a unifying, national identity.[35]

Mexican soldiers were not easily melded into an effective fighting force. Santa Anna said "the leaders of the army did their best to train the rough men who volunteered, but they could do little to inspire them with patriotism for the glorious country they were honored to serve."[36] According to leading conservative politician Lucas Alamán, the "money spent on arming Mexican troops merely enabled them to fight each other and 'give the illusion' that the country possessed an army for its defense."[37] However, an officer criticized Santa Anna's training of troops, "The cavalry was drilled only in regiments. The artillery hardly ever maneuvered and never fired a blank shot. The general in command was never present on the field of maneuvers, so that he was unable to appreciate the respective qualities of the various bodies under his command.... If any meetings of the principal commanding officers were held to discuss the operations of the campaign, it was not known, nor was it known whether any plan of campaign had been formed."[38]

At the beginning of the war, Mexican forces were divided between the permanent forces (permanentes) and the active militiamen (activos). The permanent forces consisted of 12 regiments of infantry (of two battalions each), three brigades of artillery, eight regiments of cavalry, one separate squadron and a brigade of dragoons. The militia amounted to nine infantry and six cavalry regiments. In the northern territories of Mexico, presidial companies (presidiales) protected the scattered settlements there.[39]

One of the contributing factors to loss of the war by Mexico was the inferiority of their weapons. The Mexican army was using surplus British muskets (e.g. Brown Bess) from the Napoleonic Wars period. While at the beginning of the war the majority of American soldiers were still equipped with the very similar Springfield 1816 flintlock muskets, more reliable caplock models gained large inroads within the rank and file as the conflict progressed. Some US troops carried radically modern weapons that gave them a significant advantage over their Mexican counterparts, such as the Springfield 1841 rifle of the Mississippi Rifles and the Colt Paterson revolver of the Texas Rangers. In the later stages of the war, the US Mounted Rifles were issued Colt Walker revolvers, of which the US Army had ordered 1,000 in 1846. Most significantly, throughout the war the superiority of the US artillery often carried the day. While technologically Mexican and American artillery operated on the same plane, US army training as well as the quality and reliability of their logistics gave US guns and cannoneers a significant edge.

Desertion was a major problem for the Mexican army, depleting forces on the eve of battle. Most soldiers were peasants who had a loyalty to their village and family, but not to the generals who had conscripted them. Often hungry and ill, under-equipped, only partially trained, and never well paid, the soldiers were held in contempt by their officers and had little reason to fight the invading US forces. Looking for their opportunity, many slipped away from camp to find their way back to their home village.[40]

Political divisions inside Mexico were another factor in the US victory. Inside Mexico, the centralistas and republicanos vied for power, and at times these two factions inside Mexico's military fought each other rather than the invading US Army. Another faction called the monarchists, whose members wanted to install a monarch (some advocated rejoining Spain), further complicated matters. This third faction would rise to predominance in the period of the French intervention in Mexico. The ease of the American landing at Veracruz was in large part due to civil warfare in Mexico City, which made any real defense of the port city impossible. As Gen. Santa Anna said, "However shameful it may be to admit this, we have brought this disgraceful tragedy upon ourselves through our interminable in-fighting."[41][42]

United States Army

Main article: List of U.S. Army, Navy, and volunteer units in the Mexican–American War

On the American side, the war was fought by regiments of regulars and various regiments, battalions, and companies of volunteers from the different states of the Union as well as Americans and some Mexicans in the California and New Mexico territories. On the West Coast, the US Navy fielded a battalion of sailors, in an attempt to recapture Los Angeles.[43] Although the US Army and Navy were not large at the outbreak of the war, the officers were generally well trained and the numbers of enlisted men fairly large compared to Mexico's. At the beginning of the war, the US Army had eight regiments of infantry (three battalions each), four artillery regiments and three mounted regiments (two dragoons, one of mounted rifles). These regiments were supplemented by 10 new regiments (nine of infantry and one of cavalry) raised for one year of service by the act of Congress from February 11, 1847.[44]

State volunteers were raised in various sized units and for various periods of time, mostly for one year. Later some were raised for the duration of the war as it became clear it was going to last longer than a year.[45]

US soldiers' memoirs describe cases of looting and murder of Mexican civilians, mostly by State Volunteers. One officer's diary records:

We reached Burrita about 5 pm, many of the Louisiana volunteers were there, a lawless drunken rabble. They had driven away the inhabitants, taken possession of their houses, and were emulating each other in making beasts of themselves.[46]

John L. O'Sullivan, a vocal proponent of Manifest Destiny, later recalled:

The regulars regarded the volunteers with importance and contempt ... [The volunteers] robbed Mexicans of their cattle and corn, stole their fences for firewood, got drunk, and killed several inoffensive inhabitants of the town in the streets.

Many of the volunteers were unwanted and considered poor soldiers. The expression "Just like Gaines's army" came to refer to something useless, the phrase having originated when a group of untrained and unwilling Louisiana troops were rejected and sent back by Gen. Taylor at the beginning of the war.[47]

1,563 US soldiers are buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery, which is maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Outbreak of the war

Initial skirmish at the Nueces Strip

Main article: Nueces Strip

President James K. Polk ordered General Taylor and his forces south to the Rio Grande, entering the territory that Mexicans disputed. Mexico laid claim to all the lands as far north as the Nueces River—about 150 mi (240 km) north of the Rio Grande. The U.S. claimed that the border was the Rio Grande, citing the 1836 Treaties of Velasco. However, Mexico rejected the treaties and refused to negotiate, instead still claiming all of Texas.[48] Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces. He constructed a makeshift fort (later known as Fort Brown/Fort Texas) on the banks of the Rio Grande opposite the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[49]

The Mexican forces under General Santa Anna immediately prepared for war. On April 25, 1846, a 2,000-man Mexican cavalry detachment attacked a 70-man U.S. patrol under the command of Captain Seth Thornton, which had been sent into the contested territory north of the Rio Grande and south of the Nueces River. In the Thornton Affair, the Mexican cavalry routed the patrol, killing 11 American soldiers.[50]

Regarding the beginning of the war, Ulysses S. Grant, who had opposed the war but served as an army lieutenant in Taylor's Army, claims in his Personal Memoirs (1885) that the main goal of the U.S. Army's advance from Nueces River to Rio Grande was to provoke the outbreak of war without attacking first, to debilitate any political opposition to the war.

The presence of United States troops on the edge of the disputed territory farthest from the Mexican settlements, was not sufficient to provoke hostilities. We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it. It was very doubtful whether Congress would declare war; but if Mexico should attack our troops, the Executive could announce, "Whereas, war exists by the acts of, etc.," and prosecute the contest with vigor. Once initiated there were but few public men who would have the courage to oppose it....

Mexico showing no willingness to come to the Nueces to drive the invaders from her soil, it became necessary for the "invaders" to approach to within a convenient distance to be struck. Accordingly, preparations were begun for moving the army to the Rio Grande, to a point near Matamoras (sic). It was desirable to occupy a position near the largest centre of population possible to reach, without absolutely invading territory to which we set up no claim whatever.[51]

A few days after the defeat of the U.S. troops by General Arista, the Siege of Fort Texas began on May 3, 1846. Mexican artillery at Matamoros opened fire on Fort Texas, which replied with its own guns. The bombardment continued for 160 hours[52] and expanded as Mexican forces gradually surrounded the fort. Thirteen U.S. soldiers were injured during the bombardment, and two were killed.[52] Among the dead was Jacob Brown, after whom the fort was later named.[53]

On May 8, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve the fort.[54] However, General Arista rushed north and intercepted him with a force of 3,400 at Palo Alto. The U.S. Army employed "flying artillery", their term for horse artillery, a type of mobile light artillery that was mounted on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. It had a devastating effect on the Mexican army. In contrast to the "flying artillery" of the Americans, the Mexican cannons at the Battle of Palo Alto fired at such slow velocities that it was possible for American soldiers to dodge artillery rounds.[55] The Mexicans replied with cavalry skirmishes and their own artillery. The U.S. flying artillery somewhat demoralized the Mexican side, and seeking terrain more to their advantage, the Mexicans retreated to the far side of a dry riverbed (resaca) during the night. It provided a natural fortification, but during the retreat, Mexican troops were scattered, making communication difficult.[52]

During the Battle of Resaca de la Palma the next day, the two sides engaged in fierce hand to hand combat. The U.S. Cavalry managed to capture the Mexican artillery, causing the Mexican side to retreat—a retreat that turned into a rout.[52] Fighting on unfamiliar terrain, his troops fleeing in retreat, Arista found it impossible to rally his forces. Mexican casualties were heavy, and the Mexicans were forced to abandon their artillery and baggage. Fort Brown inflicted additional casualties as the withdrawing troops passed by the fort. Many Mexican soldiers drowned trying to swim across the Rio Grande.[citation needed] Both these engagements were fought before war was declared.

Declarations of war

Outnumbered militarily and with many of its large cities occupied, Mexico could not defend itself; the country was also faced with many internal divisions, including the Caste War of Yucatán. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, by American diplomat Nicholas Trist and Mexican plenipotentiary representatives Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain, ended the war. The treaty gave the U.S. undisputed control of Texas, established the U.S.-Mexican border of the Rio Grande, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received $15 million[155] ($415 million today) – less than half the amount the U.S. had attempted to offer Mexico for the land before the opening of hostilities[156] – and the U.S. agreed to assume $3.25 million ($90 million today) in debts that the Mexican government owed to U.S. citizens.[157] The treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate by a vote of 38 to 14 on March 10, and by Mexico through a legislative vote of 51-34 and a Senate vote of 33-4, on May 19. News that New Mexico's legislative assembly had passed an act for organization of a U.S. territorial government helped ease Mexican concern about abandoning the people of New Mexico.[158]

The acquisition was a source of controversy then, especially among U.S. politicians who had opposed the war from the start. A leading antiwar U.S. newspaper, the Whig Intelligencer, sardonically concluded that "We take nothing by conquest .... Thank God."[159][160]

Jefferson Davis introduced an amendment giving the U.S. most of northeastern Mexico, which failed 44–11. It was supported by both senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party – Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray Mason of Virginia, and Ambrose Hundley Sevier – were opposed.[161] An amendment by Whig Senator George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico and Upper California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats. Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding votes for acquiring the new territories.

The acquired lands west of the Rio Grande are traditionally called the Mexican Cession in the U.S., as opposed to the Texas Annexation two years earlier, though division of New Mexico down the middle at the Rio Grande never had any basis either in control or Mexican boundaries. Mexico never recognized the independence of Texas[162] before the war, and did not cede its claim to territory north of the Rio Grande or Gila River until this treaty.

Before ratifying the treaty the U.S. Senate made two modifications: changing the wording of Article IX (which guaranteed Mexicans living in the purchased territories the right to become U.S. citizens) and striking out Article X (which conceded the legitimacy of land grants made by the Mexican government). On May 26, 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further agreed to a three-article protocol (known as the Protocol of Querétaro) to explain the amendments. The first article claimed that the original Article IX of the treaty, although replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy of land grants under Mexican law.[163] The protocol was signed in the city of Querétaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford, and Luis de la Rosa.[163]

Article XI offered a potential benefit to Mexico, in that the US pledged to suppress the Comanche and Apache raids that had ravaged northern Mexico and pay restitutions to the victims of raids it could not prevent.[164] However, the Indian raids did not cease for several decades after the treaty, although a cholera epidemic reduced the numbers of the Comanche in 1849.[165] Robert Letcher, U.S. Minister to Mexico in 1850, was certain "that miserable 11th article" would lead to the financial ruin of the US if it could not be released from its obligations.[166] The US was released from all obligations of Article XI five years later by Article II of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853.[167]

The continued story of the Mexican American War.

Abraham Lincoln as a senator was against it.

Henry David Thoreau spent his famous night in jail

over taxes for the war. Writing then "On Disobedience"

(0)

(0) (0)

(0)