Y2K 2.0: Is the US government set to “give away

Post# of 65629

Quote:

Y2K 2.0: Is the US government set to “give away the Internet” Saturday? [Update]

No. In fact, the US will still control a large swath of the 'Net.

http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2016/09/y2...-saturday/

David Kravets - 9/30/2016, 5:01 PM

UPDATE: 5:53pm EDT: A Texas federal judge Friday denied (PDF) a request by Arizona, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Texas to block the US from ceding the Internet's root zone oversight duties to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. Unless a higher court intervenes, the changeover will begin tonight at midnight EDT.

Original story:

Remember the projected Y2K bug disaster? The world's computers would supposedly go haywire as the clock ticked to January 1, 2000, thus destroying the world and ensuing widespread panic. Didn't happen. Fast forward to today, however, and another doomsday scenario is afoot (albeit with much less fanfare).

If many politicians are to be believed, an Internet disaster is set to commence this Saturday. That's when a tiny branch of the US Commerce Department officially hands over its oversight of the Internet's "address book" or root zone—the highest level of the domain naming system (DNS) structure—to a nonprofit, a Los Angeles-based body called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN).

Calling it an "Internet giveaway," many Republican lawmakers tried to block the changeover, a transition that is strongly supported by the President Barack Obama administration and by Internet giants like Facebook and Google.

"Today our country faces a threat to the Internet as we know it... If Congress fails to act, the Obama administration intends to give away the Internet to an international body akin to the United Nations," said lawmaker Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) in a recent speech on the Senate floor. "I rise today to discuss the significant, irreparable damage this proposed Internet giveaway could wreak not only on our nation but on free speech across the world."

The campaign of Donald Trump, the GOP presidential candidate, offered similar words:

"The Republicans in Congress are admirably leading a fight to save the Internet this week, and need all the help the American people can give them to be successful. Congress needs to act, or Internet freedom will be lost for good, since there will be no way to make it great again once it is lost."

But ICANN, the Commerce Department, and plenty of others, have scoffed at the assertion made by Cruz, Trump, and countless others.

"The US government has never, and has never had the ability to, set the direction of the (ICANN) community’s policy development work based on First Amendment ideas," ICANN said in a statement. "Yet that is exactly what Senator Cruz is suggesting.

The US government has no decreased role. Other governments have no increased role. There is simply no change to governmental involvement in policy development work in ICANN."

Cruz has a scary looking website with a countdown clock leading to October 1. With the changeover imminent, US lawmakers have been haggling over the issue all week. Some, like Cruz, have even attempted to slip language barring the transition into legislation for continuing to fund the US government.

But late Wednesday, that attempt failed. Conveniently, the government's fiscal year ends September 30, the same day the Commerce Department's oversight of the global DNS is terminated.

One other hurdle remains. A last-minute federal lawsuit (PDF) brought by Arizona, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Texas. The attorneys general for those states are seeking a court order from a federal judge to block the move. A hearing has been set for Friday afternoon. "Trusting authoritarian regimes to ensure the continued freedom of the Internet is lunacy," Ken Paxton, the Texas attorney general, said.

Overall opposition to the transition appears to be largely political. Many GOP lawmakers (and the Trump campaign) are seemingly arguing that without US oversight, foreign governments or hacking groups from the Internet's dark corners might take over, control the Internet, and censor it dramatically. What's more, these critics suggest that without US oversight, the Internet's infrastructure might crumble entirely. The World Wide Web would be left in a state of anarchy.

That simply isn't true. Ask other US officials, tech companies, or even Internet architects who helped build the current system, and they'll say the US government's oversight role of the Internet is too small for such doomsday scenarios to occur. In fact, these proponents of the transition even say that leaving the root zone under US control could cause more harm than good in the long run.

Rhetoric aside, US retains vast Internet control

Regardless of who's right or wrong in the ICANN changeover debate, one thing nobody can deny is that the United States will continue exercising a powerful hold over a great swath of the Internet—even under the transition.

That's because the companies that oversee the world's most popular top-level domains (.com, .org, and .net) are based in the United States. These organizations must follow US law and abide by US court orders, and they have to remove websites from the global Internet when ordered to do so.

To date, these court orders are how the US government has seized thousands of websites it has declared to be breaking laws about intellectual property, drugs, gambling, and you name it. Kim Dotcom's Megaupload file-sharing site fell because of this in 2012. The Bodog online sports wagering site was shuttered by the US that same year even though that .com domain was purchased with a Canadian register.

What's more, even when a domain is registered under a handle that is outside of the United States' official jurisdiction, the US government has international cooperation agreements with many countries that require foreign registries to abide by US directives.

The most high-profile case of this kind was this summer's shuttering of one of the world's most notorious file-sharing sites—KAT.cr, or the KickassTorrents website. While the site had been playing a game of Internet domain Whac-a-mole to retain a leg up on global intellectual property authorities, it was registered with the .cr domain by the Costa Rican register called NIC when it was shuttered at the request of the US.

The site's alleged operator was arrested in July in Poland and charged by US authorities with varying criminal copyright infringement counts.

Enlarge

The US often leaves a landing page on shuttered sites notifying Web surfers that sites were "seized pursuant to an order issued by a US District Court." Whether you call it censorship or just following the law, countries across the globe have similar domain-seizing powers that won't be disturbed by the ICANN changeover.

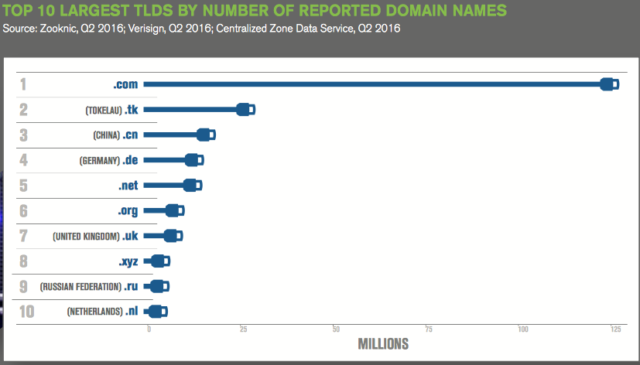

The fact that .com, .net, and .org sites are run by US-based companies isn't trivial, either. Verisign, of Virginia, maintains the global DNS Internet root zone system at the center of the ICANN transition debate, and the company has an indefinite contractual right from ICANN to manage the globe's .com and .net domains. About 127 million of the world's 334 million top-level domain name registrations worldwide are .com, according to Verisign. The .net domain comes in fifth place worldwide, and .org is sixth place. The .org domain is operated by the Public Interest Registry, also of Virginia.

Enlarge

So what is this ICANN transition about?

The most simple answer is that a branch of the US Commerce Department will no longer have technical oversight of a contract (PDF) with ICANN and Verisign over the maintenance of the Internet's DNS. Just like its endless deal to manage .com and .net, ICANN has already ceded Verisign the indefinite contractual rights (PDF) to manage the global Internet's DNS root zone. Verisign can only lose the rights to renew these contracts if it doesn't perform.

At its most basic level, the DNS allows Internet surfers to input "arstechnica.com" into a Web browser to render the Ars news site. Absent such a coordinated, worldwide naming system, Internet surfers would have to type in Ars' real IP address: (50.31.151.33). Verisign said its DNS average daily query load was approximately 130 billion queries for the second quarter of 2016, up 17 percent year over year. (Verisign declined to comment for this story.)

ICANN was created in 1998 to take over the job of essentially a single person, Jon Postel, who is now deceased and was often referred to as the "God of the Internet." He had run the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

That agency (PDF) was consumed by the US National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), a branch of the US Commerce Department. The NTIA says it only has a "procedural role" in approving zone changes, and the group says it has been planning to remove itself from this role for nearly two decades in order to cede that responsibility to ICANN, which has an organizational chart that would put most private industry to shame.

Essentially, this oversight is all that is left of the US government's control of the DNS. Under the transition, the feds will no longer have that role when October begins.

Here's what the NTIA told Ars in a recent e-mail:

The IANA transition is the final step in a nearly 20-year process to privatize the Internet domain name system. Two years ago, NTIA announced it would transition our stewardship role related to the Internet domain name system to the Internet multistakeholder community, which includes businesses, technical experts, academics, civil society groups, and other stakeholders.

This move will help ensure that the stakeholders who own and operate, transact business, and exchange information over the myriad of networks that comprise the Internet will continue to make decisions about the technical underpinnings of the Internet just as they do today.

The transition will help preserve and strengthen this multistakeholder approach that has helped make the Internet an engine for economic growth, innovation, and free expression.

Government-speak aside, here's what's really happening: when there is a root zone change request from a domain registry, for example, this needs to be approved by the Commerce Department's NTIA "before Verisign can act on it," Akram Atallah, ICANN's president of the global domains division, told Ars in a recent interview.

"In reality, the only thing that really changes is that NTIA will no longer approve these changes. We will send them to Verisign, and Verisign will have to update the root zone," he said.

According to Atallah, the system works like this: suppose the operator of the .ru domain in Russia, or Egypt's .eg, wants to add an IP address to a new server or wants to change an IP address because a server went down. He said the operators of those domains would send ICANN a request "to add a root zone file change," which is essentially a change in the global Internet address book. This same thing needs to happen when new generic, top-level domains are rolled out, such as .store or .book and dozens of others.

"We send this to Verisign to put in the root zone file. NTIA has to approve this action before Verisign can update the root zone file," Atallah said, explaining how the system works under the Commerce Department's oversight.

For its part, NTIA explains its oversight role as this: ICANN comes to NTIA with a root zone change request. NTIA verifies that ICANN followed established protocol for that change, and then NTIA authorizes the root zone change. NTIA's briefing paper (PDF) about the DNS oversight role it is ceding is public and explains things in more granular detail.

In all, the NTIA signed off on 1,513 root zone changes last year. This year, there have been 1,051 so far.

"The US government was really never very hands on in terms of its oversight," said Jeremy Malcolm, a policy analyst with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "Someone had to be there to make sure that the right processes were being followed so the organization could run. Its role was not of how it runs, but of ensuring it runs true to its founding objectives and that it remains accountable and transparent."

Atallah believes ICANN is now ready to take over that role. "We have tested and demonstrated that we can do this," he said. And Atallah thinks it makes good business sense for Verisign to enjoy an indefinite contract, which includes a maximum $7.85 for each .com registration. Under a competitive landscape, he said, companies may not want to go the extra mile, "because they have no assurances if they invest heavily in the business they will be able to reap the benefits."

Atallah said both Verisign and the NTIA have to follow the contractual rules, meaning that neither the NTIA nor Verisign has the power to act on its own—preventing things like unilaterally meddling with the Internet's DNS zoning system to comport with their own wills. For that matter, ICANN must follow its own rules, too, and it cannot cede to pressure from any single government. For example, the US government tried to exert its power over ICANN to block it from implementing the .xxx domain, but ICANN approved it anyway in 2011.

"Sore point" for others

ICANN—which is composed of a multitude of Internet stakeholders, international governments, and technologists—has issued its own report on the transition:

The proposal eliminates NTIA’s verification and authorization role for root zone changes, and IANA functions performance oversight is replaced with direct customer stewardship via contracts, service-level expectations, community-led reviews, and increased transparency. The accountability provisions maintain the advisory role of governments within ICANN, and through bylaw changes, ensure that a government or a group of governments cannot capture or exercise undue influence over the DNS.

In short, many people familiar with the transition describe it as a "symbolic" changeover. They say it will relieve, whether real or perceived, thoughts from the global community that the United States maintains the Web. In 2011, for example, Russia's Vladimir Putin suggested ICANN could be taken over by the International Telecommunications Union, a branch of the United Nations.

"If we are going to talk about the democratization of international relations, I think a critical sphere is information exchange and global control over such exchange," Putin said at the time.

Atallah acknowledged that the Commerce Department's involvement "is a sore point for a lot of other governments." That's a mindset Vint Cerf, Google's Internet evangelist and former ICANN chairman, also holds. "It's time to show that the Internet doesn't require government oversight," Cerf told Bloomberg. "Other governments look at that and ask why should the US government have this special position. It isn't necessary any more."

The changeover also has the backing of some of the world's leading, US-based tech companies, such as Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Twitter. They said it was "imperative" that Congress doesn't block the move.

"A global, interoperable and stable Internet is essential for our economic and national security, and we remain committed to completing the nearly twenty year transition to the multi stakeholder model that will best serve US interests," a letter from the companies to leaders of Congress said. Even the conservative US Chamber of Commerce supports the transition.

But others, like Theresa Payton, the former White House chief information officer and now the CEO of security company Fortalice Solutions, paint a doomsday scenario. If the Commerce Department cedes control, she said, "the United States cannot be assured that if any website is hacked, the responsible party will be held accountable."

We cannot be sure if a website is valid. We cannot be sure if one country is being favored over another. These are all the things ICANN is responsible for and has worked perfectly since the Internet was created. Why change it now and so close to the election?

The evil empire

Will ICANN become the evil empire come Saturday because a tiny wing of the US Commerce Department won't be there to rubberstamp root zone changes? Will ICANN suddenly become so drunk with power that a man behind an ICANN secret curtain will flip a switch and ruin the global Internet as we know it?

Remember, the Y2K bug was going to cause nuclear annihilation as the year 2000 commenced—or, at a minimum, there would be no electricity, heat, or running water. None of that turned out to be true despite major rhetoric.

If your browser is able to point to this story Saturday, none of the ICANN transition fears immediately came true, either .

(1)

(1) (0)

(0)