CDOC..Big things happening with giant players..

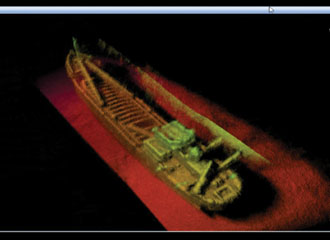

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Underwater Imaging System (UIS) displays 3-D imagery of a sunken vessel.

A precision imaging system is poised to gain wider exposure.

In a few months, the U.S. Coast Guard will complete its evaluation of an underwater 3-D imaging system that will then be transferred from the service’s Research and Development Center to operators. But even as the technology is being assessed, the system is deploying to hot spots around the world, most recently in the search for bodies following the late February crash of a Coast Guard helicopter off the coast of Alabama.

The Underwater Imaging System (UIS) is a fully integrated 3-D sonar system for specialized underwater applications such as maritime security, port and harbor maintenance, search and recovery, and intruder visualization and classification. The system also can be used to rapidly assess storm damage, locate sunken debris and provide baseline maps of critical infrastructure. It delivers precise Global Positioning System-referenced underwater scans in real time and can be used for inspections of harbor walls, bulkheads, piers, bridges, pilings and ship hulls. The system also can be used to inspect and clear shipping channels and to image and classify underwater objects.

The Coast Guard Research and Development Center uses a two-person team—one to operate the system, the other to record data. The UIS is attached to a vessel’s hull and lowered on a pole. It also can be raised, pivoted or canted at specific angles as necessary.

The system recently was deployed when a Coast Guard helicopter crashed near the Mobile, Alabama, shore. The flight originated from the Coast Guard Aviation Training Center in Mobile and crashed into Mobile Bay about three miles southwest of Point Clear. Service officials determined that underwater visibility was too poor for divers to locate the four lost crew members. The UIS was deployed to aid in the search, and ultimately all four bodies were recovered. “The UIS has been a major contributor in the search for lost souls, as well as to map the underwater debris field—in part because the turbidity of the water is so bad that divers can’t see,” explains Jack McCready, branch chief for the Coast Guard Research and Development Center’s Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) branch.

The Coast Guard has deployed the system through an on-demand process for several real-world operations since it began evaluating the UIS in 2006. “It was also utilized during the recovery of 7½ tons of cocaine from a sunken self-propelled semisubmersible last summer,” McCready reports. “The Coast Guard cutter Oak used its side-scan sonar system in wide area search modality, and it was able to provide several possible locations. As the cutter moved to each of these locations, the UIS was then able to conduct precise imaging.” When the system found the sunken vessel, it was able to direct a team of FBI divers exactly to the target.

In that case, the Coast Guard cutter Seneca intercepted the submersible vehicle off the Honduran coast, detained the crew and recovered some of the cargo before the boat sank. The cocaine was recovered from the sunken vessel in what Coast Guard officials described as a first-of-its-kind operation.

The UIS system also has been called to assess subsurface damage to a navigational aid structure after it was struck by a freighter and to document oil density following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. It also was deployed to support the shallow water search for a boating accident victim off of Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. In that case, the body was located in a different area, away from where the UIS was deployed.

The system currently is in the operational assessment phase, which ends in September. “We have completed the necessary research and development. We are collecting some final reliability information, and we are conducting operational assessments in preparation for transitioning this to a program of record,” McCready says. Once the operational assessment period is complete, the Research and Development Center officially will transfer the five systems under evaluation to Coast Guard operators, and service leadership will use information provided by the center to determine whether to seek the necessary funding to make it a program of record. The funding would be applied to final operational test and evaluation, as well as logistics, sustainment and maintenance. If the utility of the UIS is realized, the Coast Guard eventually may decide to purchase more.

The UIS began its journey with the Coast Guard when the 109th Congress directed the service to evaluate the Echoscope sonar head made by CodaOctopus Products Limited, Edinburgh, United Kingdom. The system has since evolved into the UIS. The evolution has included enhancing the processing capability and adapting algorithms for image processing using high-frequency Doppler sonar. “What started off as an underwater sonar head has now translated into a highly accurate 3-D imaging system. One of the unique things that happened during the evolution is the application of real-time kinematics,” McCready says. “We could be offshore—say two or three hundred yards—and imaging into port. The real-time kinematics translates exactly where that image is in distance from the sonar head. So, when you have an object of concern, it precisely translates the object’s actual location.”

The Coast Guard used the UIS in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to help assess oil density in the water.

The precision location capability comes in handy for change detection following a natural disaster, for example. Following an event such as the recent earthquake in Haiti or Hurricane Katrina, the UIS can help users determine whether port damage will impede operations, McCready explains. Additionally, users could image along a major pier, such as those in New York or Los Angeles, and then image again a week later, allowing them to detect new or uncovered objects. It also can assist divers in locating and identifying suspicious and possibly dangerous objects. “I would be hesitant to say I can find explosives, because it is not used in that way. It is used in a port and waterway security environment to identify objects of concern. It helps in identifying targets of interest so that we can then send down divers for inspection. If you see something in the shape of a 55-gallon drum with wires sticking out of it, you would be concerned,” McCready says.

He differentiates between the UIS sonar and the wide area sonar typically used by the U.S. Navy. The primary differences are in how the Coast Guard uses the system, precision and the ability for shallow water operations. The UIS detects and locates objects within millimeters. In addition, it operates in waters as shallow as two feet.

McCready says the Coast Guard evaluated and compared other types of underwater imagers—lasers and cameras with lighting systems—but the UIS came out on top. “We evaluate across the spectrum to identify the best method of being able to interrogate and to create an image, so we have looked at multiple technologies,” McCready explains.

CodaOctopus recently announced that it delivered the UIS to the Netherlands’ survey department, Rijkswaterstaat, which will use it for such tasks as lock and dam inspections and canal floor debris evaluation work. It also may be used for performing minimum clearance investigations above shipwreck sites in shipping channels. The system is used by a number of U.S. law enforcement and port security organizations, including the Alameda County Sheriff’s Department in California and the Boston Police Department, according to information provided by the company.

WEB RESOURCES

Coast Guard Research and Development Center: www.uscg.mil/acquisition/rdc/rdc.asp

CodaOctopus: www.codaoctopus.com