(Total Views: 207)

Posted On: 09/21/2022 4:18:14 PM

Post# of 128431

How police work with Google to obtain cellphone location data for criminal investigations

The process begins with anonymous information and can progress to include names and emails connected to phones located near a crime scene.

With help from Google, police can drop a virtual dragnet over crime scenes that locate people’s phones within about 10 feet of accuracy.

A warrant launches a three-step process, which starts with the tech giant providing anonymous information and can progress to include names and emails connected to a subset of targeted phones.

The practice raises concerns about invasion of privacy and questions about whether geofence results actually solve crimes.

Details of how police and tech companies work together, and how rigorous the courts are before issuing warrants, remain scant.

Cold cases cracked by cellphones: Police are using geofence warrants to solve crimes.

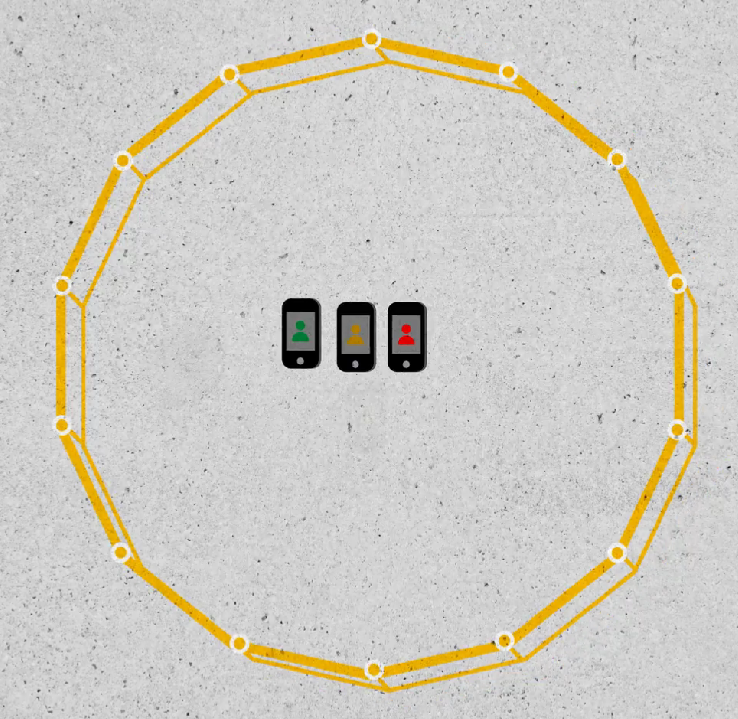

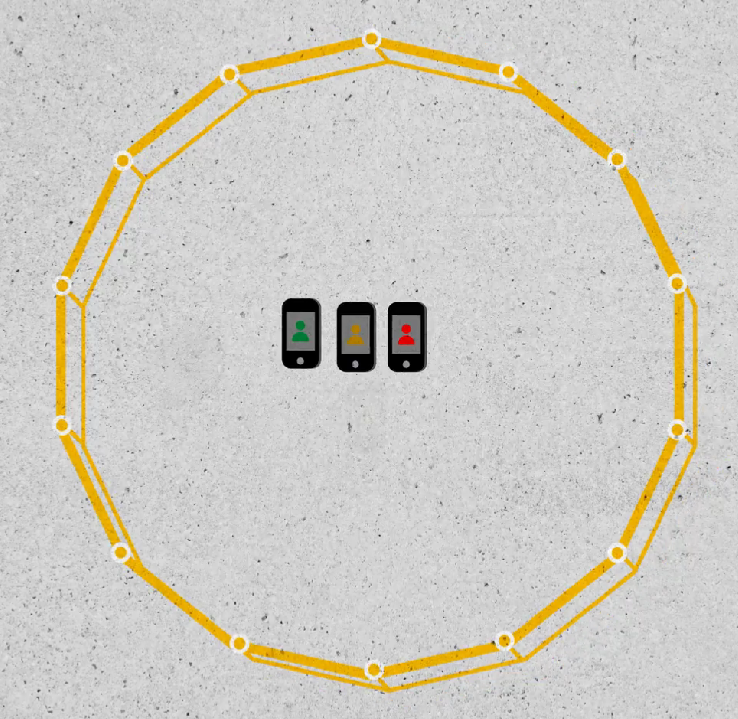

Google then is served a warrant to disclose a list of de-identified device numbers, latitude and longitude coordinates and a timestamp of users who location history data indicates were within the geofence during that time frame.

Next, police review the de-identified data to determine devices of interest.

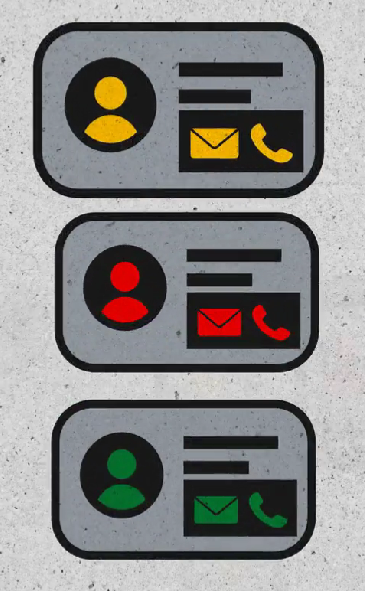

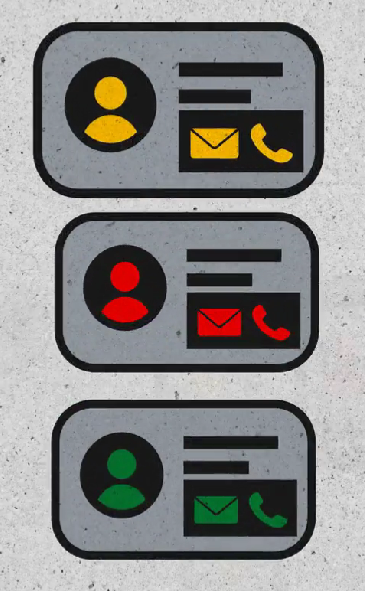

If the detectives find a lead, they can compel Google to provide account-identifying information such as names and emails associated with the accounts.

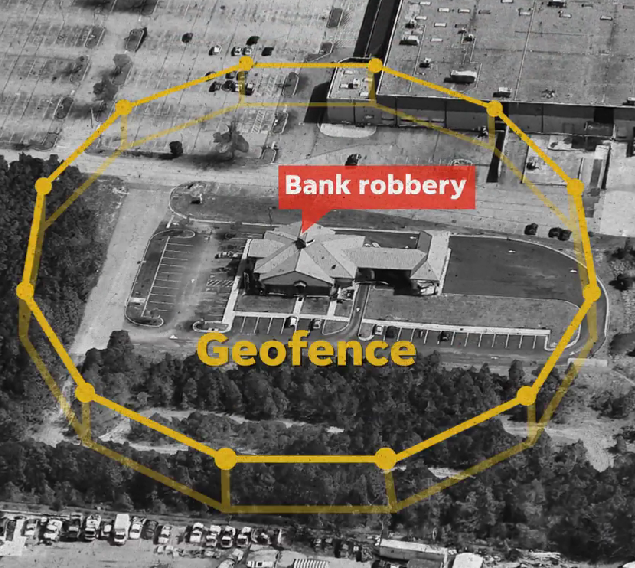

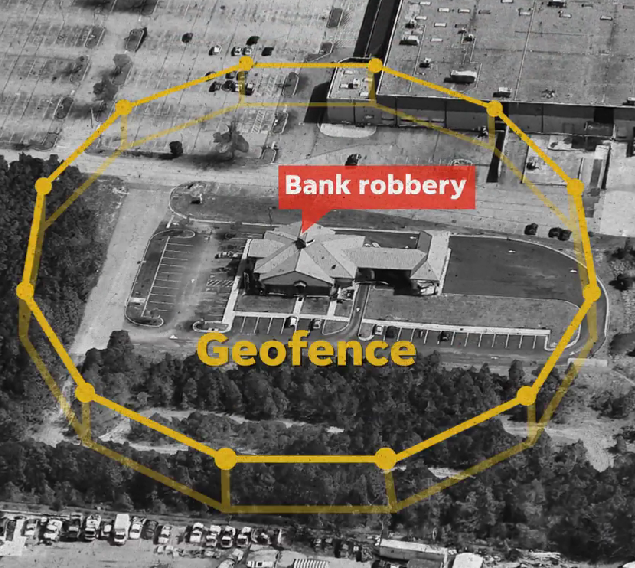

In Virginia, a police detective applied for a geofence warrant three weeks after the bank robbery, which was granted by a Chesterfield County magistrate judge. The geofence captured a 150-meter radius, longer than three football fields, around the bank. Detectives requested data from 4:20 to 5:20 p.m. on the day of the robbery.

Google came back with de-identified information on 19 devices at 210 location points.

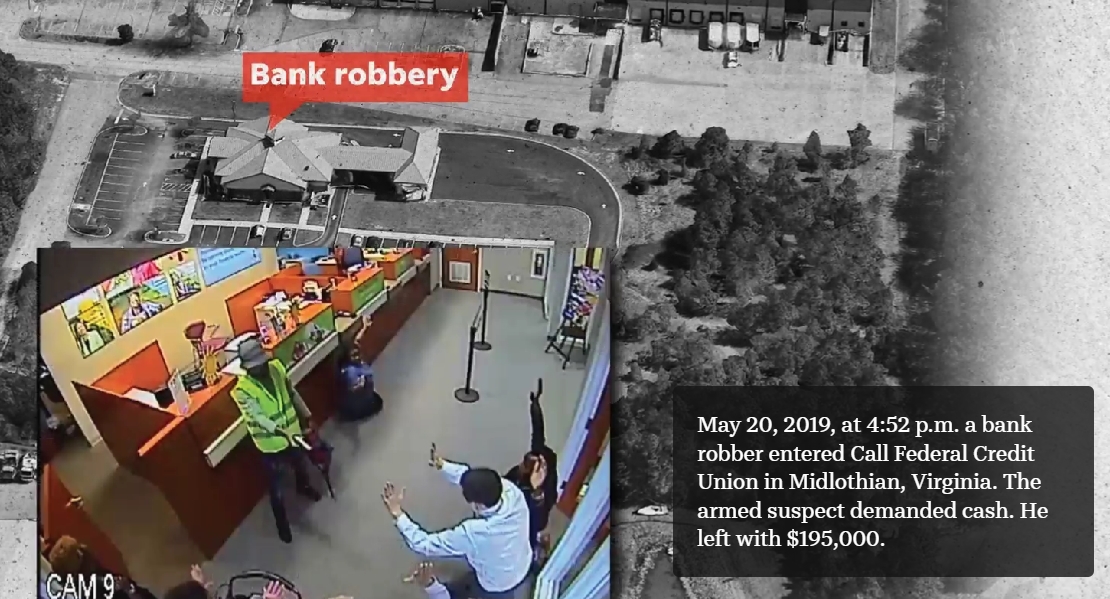

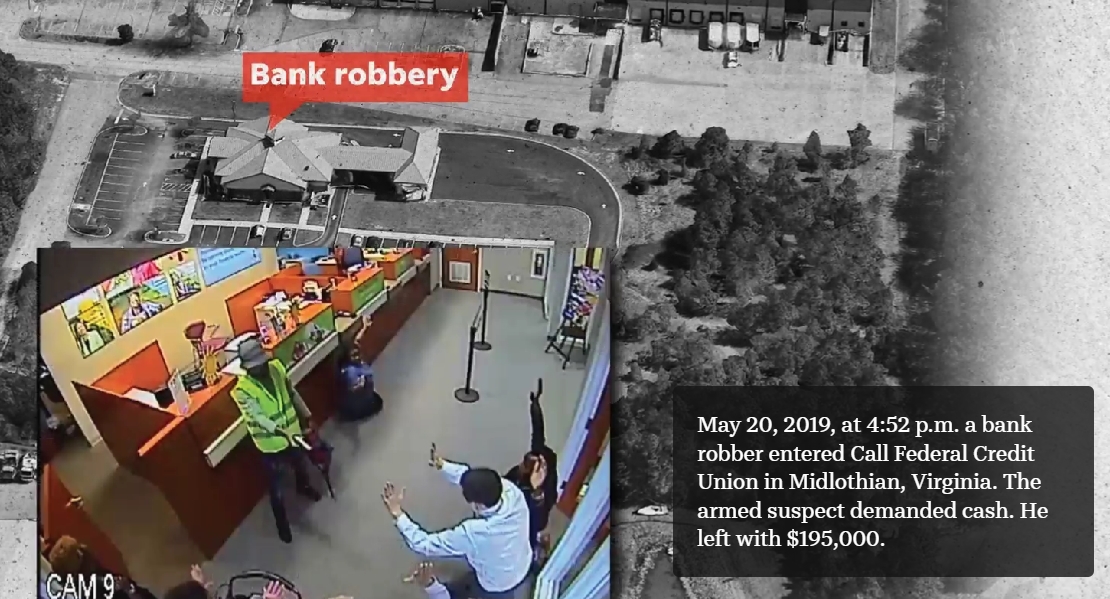

May 20, 2019, at 4:52 p.m. a bank robber entered Call Federal Credit Union in Midlothian, Virginia. The armed suspect demanded cash. He left with $195,000.

Detectives opted to rely on a technique called a geofence, which begins with identifying where and when a crime occurred and drawing a virtual fence around it.

The next step requires applying for a search warrant with a local judge, often a magistrate, to request all “Location History” data from Google for all users who were within that area during that time.

Google then is served a warrant to disclose a list of de-identified device numbers, latitude and longitude coordinates and a timestamp of users who location history data indicates were within the geofence during that time frame.

Next, police review the de-identified data to determine devices of interest.

If the detectives find a lead, they can compel Google to provide account-identifying information such as names and emails associated with the accounts.

In Virginia, a police detective applied for a geofence warrant three weeks after the bank robbery, which was granted by a Chesterfield County magistrate judge. The geofence captured a 150-meter radius, longer than three football fields, around the bank. Detectives requested data from 4:20 to 5:20 p.m. on the day of the robbery.

Google came back with de-identified information on 19 devices at 210 location points.

Detectives then narrowed that list down to nine suspects.

From that list detectives asked for identifying information, such as names and emails associated with the accounts, for three devices.

This identifying step led to Okello T. Chatrie, 24. He was arrested and indicted by a grand jury on two counts of armed robbery. On Aug. 10, 2022, a judge sentenced Chatrie to nearly 12 years in prison.

Surveillance cameras captured the loud thump of bicyclist Pamela Morehouse being hit from behind on a Sunday evening bike ride in Crescent City, California, three miles from the Pacific Ocean near the Oregon state line.

Witnesses heard a manual transmission truck rushing through its gears while screeching away – but didn’t catch a good glimpse.

The driver who called 911 had found Morehouse facedown on the shoulder of the road, her pulse fading. Morehouse, 55, died at a nearby hospital with broken ribs and neck and a brain hemorrhage.

For months, all police had was that footage. It showed a crumpled orange bike and a dark-colored pickup speeding from the scene, but its license plate number was not visible.

But using cell phone tracking they were able to track down the killer.

Warrants must be approved by a judge and initial data is anonymous, but names typically come later

Details are scant on how police and Google work together

The practice raises privacy and accuracy concerns for citizens

https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/invest...242998002/

The process begins with anonymous information and can progress to include names and emails connected to phones located near a crime scene.

With help from Google, police can drop a virtual dragnet over crime scenes that locate people’s phones within about 10 feet of accuracy.

A warrant launches a three-step process, which starts with the tech giant providing anonymous information and can progress to include names and emails connected to a subset of targeted phones.

The practice raises concerns about invasion of privacy and questions about whether geofence results actually solve crimes.

Details of how police and tech companies work together, and how rigorous the courts are before issuing warrants, remain scant.

Cold cases cracked by cellphones: Police are using geofence warrants to solve crimes.

Google then is served a warrant to disclose a list of de-identified device numbers, latitude and longitude coordinates and a timestamp of users who location history data indicates were within the geofence during that time frame.

Next, police review the de-identified data to determine devices of interest.

If the detectives find a lead, they can compel Google to provide account-identifying information such as names and emails associated with the accounts.

In Virginia, a police detective applied for a geofence warrant three weeks after the bank robbery, which was granted by a Chesterfield County magistrate judge. The geofence captured a 150-meter radius, longer than three football fields, around the bank. Detectives requested data from 4:20 to 5:20 p.m. on the day of the robbery.

Google came back with de-identified information on 19 devices at 210 location points.

May 20, 2019, at 4:52 p.m. a bank robber entered Call Federal Credit Union in Midlothian, Virginia. The armed suspect demanded cash. He left with $195,000.

Detectives opted to rely on a technique called a geofence, which begins with identifying where and when a crime occurred and drawing a virtual fence around it.

The next step requires applying for a search warrant with a local judge, often a magistrate, to request all “Location History” data from Google for all users who were within that area during that time.

Google then is served a warrant to disclose a list of de-identified device numbers, latitude and longitude coordinates and a timestamp of users who location history data indicates were within the geofence during that time frame.

Next, police review the de-identified data to determine devices of interest.

If the detectives find a lead, they can compel Google to provide account-identifying information such as names and emails associated with the accounts.

In Virginia, a police detective applied for a geofence warrant three weeks after the bank robbery, which was granted by a Chesterfield County magistrate judge. The geofence captured a 150-meter radius, longer than three football fields, around the bank. Detectives requested data from 4:20 to 5:20 p.m. on the day of the robbery.

Google came back with de-identified information on 19 devices at 210 location points.

Detectives then narrowed that list down to nine suspects.

From that list detectives asked for identifying information, such as names and emails associated with the accounts, for three devices.

This identifying step led to Okello T. Chatrie, 24. He was arrested and indicted by a grand jury on two counts of armed robbery. On Aug. 10, 2022, a judge sentenced Chatrie to nearly 12 years in prison.

Surveillance cameras captured the loud thump of bicyclist Pamela Morehouse being hit from behind on a Sunday evening bike ride in Crescent City, California, three miles from the Pacific Ocean near the Oregon state line.

Witnesses heard a manual transmission truck rushing through its gears while screeching away – but didn’t catch a good glimpse.

The driver who called 911 had found Morehouse facedown on the shoulder of the road, her pulse fading. Morehouse, 55, died at a nearby hospital with broken ribs and neck and a brain hemorrhage.

For months, all police had was that footage. It showed a crumpled orange bike and a dark-colored pickup speeding from the scene, but its license plate number was not visible.

But using cell phone tracking they were able to track down the killer.

Warrants must be approved by a judge and initial data is anonymous, but names typically come later

Details are scant on how police and Google work together

The practice raises privacy and accuracy concerns for citizens

https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/invest...242998002/