(Total Views: 359)

Posted On: 06/04/2021 2:57:18 PM

Post# of 129006

Selling Snake Oil, Then & Now: The Truth About Lies (with Aja Raden)

The illusion of honesty and the evolution of deceit.

Greg Olear

Jun 4

CORPORATIONS ENJOY MONOPOLIES over key industries. Despite some action taken by Congress, neither the outgoing Republican president nor the incoming Democrat is eager to intervene at the federal level.

Spurred by an unprecedented spike in commercial advertising, pharmaceutical sales boom—resulting in a pervasive opioid crisis that dovetails with a nationwide alcohol-abuse problem.

A two-year recession culminates in a full-fledged panic, with unemployment as high as 18.4 percent.

Immigrants of a visibly different race work the manual-labor jobs the natives do not want, and are reviled for it. The immigrants are clean-shaven, while the native men wear wild facial hair.

The marriage of a British prince, the likely successor to the aged and long-reigning Queen, captures international headlines.

Way too many Americans get their news from a suspect press, more focused on sensationalism than serious reportage.

Surprise! I’ve set this up to trick you into thinking I’m talking about the here and now—which deception is on point for this week’s podcast—but actually, I’m writing about 1893. It was a helluva year:

The three-year-old Sherman Antitrust Act was not the monopoly-busting weapon it would become.

Grover Cleveland and his walrus ‘stache re-assumed possession of the refurbished White House, replacing the forgettable Benjamin Harrison and his Santa Claus beard.

Men were getting so drunk so often that women began starting up temperance organizations devoted to the prohibition of alcohol.

The future George V tied the knot.

The Panic of 1893 went down.

Chinese immigrants, who were building the railroad, brought with them a topical remedy for aches and pains. As Aja Raden explains in her new book, The Truth About Lies: The Illusion of Honesty and the Evolution of Deceit: “The original Chinese snake oil was made from the rendered fat of black water snakes, also called the black water moccasin.

It was a transdermal, lipophilic agent with an extraordinary concentration of omega-3 acids, which really did reduce pain and inflammation.” The imported snake oil was shared by the Chinese laborers, and when they left, that was the end of the miracle cure, black water moccasins not being native to the U.S. But everyone knew what snake oil was, and that it worked.

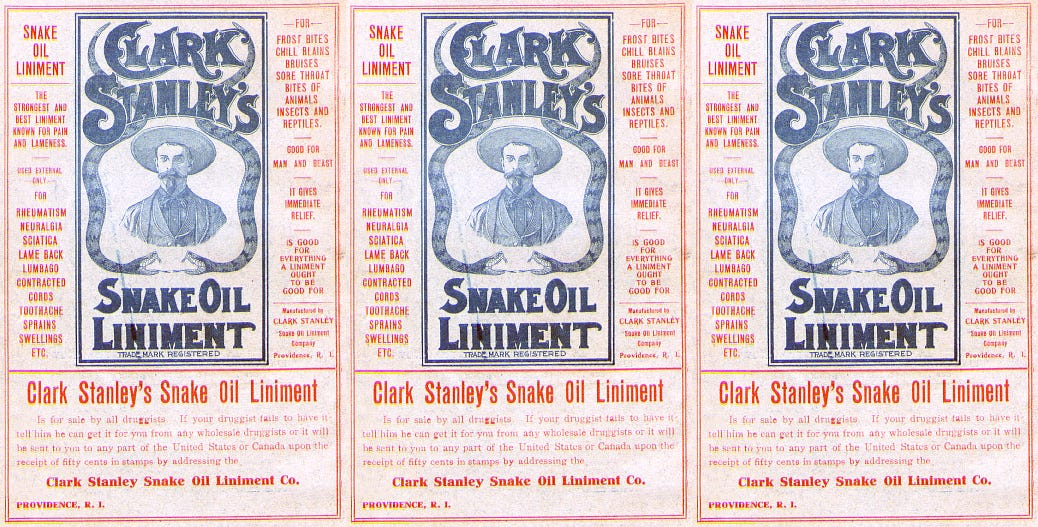

In 1893, at the legendary Chicago World’s Fair, a well-mustachioed Wild West showman named Clark Stanley put on a show for the ages, producing a (supposedly) live rattlesnake from a bag, fileting it, and then, with a theatrical flourish, hurling it into a pot of boiling water. This, Stanley told the astonished crowd, is how you make snake oil! The World’s Fair appearance began an unprecedented advertising blitz.

It was impossible to pick up a periodical and not read about Stanley’s Snake Oil. The self-styled Rattlesnake King claimed to have “learned about the secret ancient formula of rattlesnake oil from Hopi medicine man,” Raden writes. “And that tracks, because Hopi medicine men definitely tell random trespassing white people stuff like that.”

Clark Stanley may not have invented snake oil, Raden argues, but he did pioneer the mass marketing of pharmaceuticals, to disastrous effect. His much-ballyhooed formula was mostly turpentine (!). But other patent medicines, which unlike snake oil were meant to be ingested, contained substances like cocaine, opium, mercury, lead, arsenic, and, incredibly, radium.

These proto-Goop concoctions were sold everywhere. Coca-Cola was marketed as a brain tonic, and it kind of was, because it had fucking cocaine in it. Many if not most tonics for premenstrual women and fussy babies contained heroin (which, to be fair, did help the cramps and calm the infants). Snake oil led to the nation’s first opioid crisis.

By 1893, William Randolph Hearst had already entered the field of newspaper publishing. His purchase of the New York Journal and subsequent poaching of the top talent at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World led to a “yellow journalism” arms race, with each publication trying to outdo the other with the luridness and font-size of its headlines: clickbait for the 19th century.

This came to a head in 1897, when Hearst, eager for a war with Spain because war is good for sales, dispatched the artist Frederic Remington to Spanish-controlled Cuba. “There will be no war,” Remington cabled his boss, to which Hearst famously replied: “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” A year later, the U.S. did indeed go to war with Spain, the appetite for which was catalyzed by Heart’s papers. (Remember the Maine?)

The Journal and the World are long gone, but people still read their competitor, which built its reputation on a promise made in 1897 to provide “all the news that’s fit to print”—and, implicitly, none that isn’t: the New York Times. Harrison, Cleveland, and William McKinley gave way to a president who was willing to take on big business: Theodore Roosevelt. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 mandated that anything containing alcohol, morphine, heroin, opium, cocaine, eucaine, chloroform, cannabis indica, chloral hydrate, and acetanilide had to say so on the package.

“The law,” Raden writes, “basically the No Roofies / No Duds Act of 1906, also strictly prohibited advertising the presence of any ingredients that were not present in the product—like actual snake oil in Stanley’s Snake Oil.” That drove the Rattlesnake King out of business, and created an enduring cliché.

True, Facebook and Fox News are more powerful than broadsheet print ads, the Times isn’t what it used to be, and if we want opiates, we have to get them from a doctor, a dealer, or a Sackler. But we’ve been here before. And what will deliver us from 2021 is the same thing that delivered us from 1893: the truth—with a big assist from the federal government.

https://gregolear.substack.com/p/selling-snak...v8iu8INI-A

The illusion of honesty and the evolution of deceit.

Greg Olear

Jun 4

CORPORATIONS ENJOY MONOPOLIES over key industries. Despite some action taken by Congress, neither the outgoing Republican president nor the incoming Democrat is eager to intervene at the federal level.

Spurred by an unprecedented spike in commercial advertising, pharmaceutical sales boom—resulting in a pervasive opioid crisis that dovetails with a nationwide alcohol-abuse problem.

A two-year recession culminates in a full-fledged panic, with unemployment as high as 18.4 percent.

Immigrants of a visibly different race work the manual-labor jobs the natives do not want, and are reviled for it. The immigrants are clean-shaven, while the native men wear wild facial hair.

The marriage of a British prince, the likely successor to the aged and long-reigning Queen, captures international headlines.

Way too many Americans get their news from a suspect press, more focused on sensationalism than serious reportage.

Surprise! I’ve set this up to trick you into thinking I’m talking about the here and now—which deception is on point for this week’s podcast—but actually, I’m writing about 1893. It was a helluva year:

The three-year-old Sherman Antitrust Act was not the monopoly-busting weapon it would become.

Grover Cleveland and his walrus ‘stache re-assumed possession of the refurbished White House, replacing the forgettable Benjamin Harrison and his Santa Claus beard.

Men were getting so drunk so often that women began starting up temperance organizations devoted to the prohibition of alcohol.

The future George V tied the knot.

The Panic of 1893 went down.

Chinese immigrants, who were building the railroad, brought with them a topical remedy for aches and pains. As Aja Raden explains in her new book, The Truth About Lies: The Illusion of Honesty and the Evolution of Deceit: “The original Chinese snake oil was made from the rendered fat of black water snakes, also called the black water moccasin.

It was a transdermal, lipophilic agent with an extraordinary concentration of omega-3 acids, which really did reduce pain and inflammation.” The imported snake oil was shared by the Chinese laborers, and when they left, that was the end of the miracle cure, black water moccasins not being native to the U.S. But everyone knew what snake oil was, and that it worked.

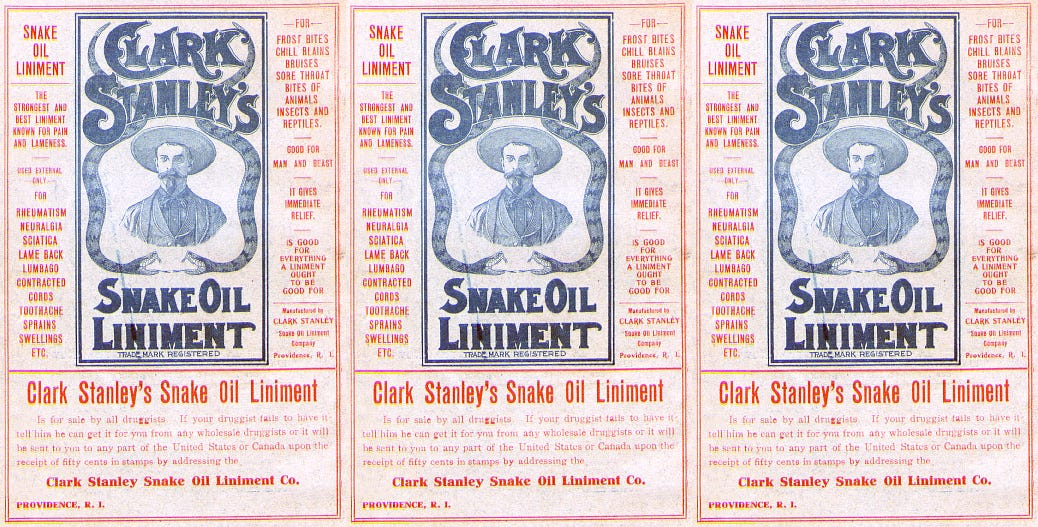

In 1893, at the legendary Chicago World’s Fair, a well-mustachioed Wild West showman named Clark Stanley put on a show for the ages, producing a (supposedly) live rattlesnake from a bag, fileting it, and then, with a theatrical flourish, hurling it into a pot of boiling water. This, Stanley told the astonished crowd, is how you make snake oil! The World’s Fair appearance began an unprecedented advertising blitz.

It was impossible to pick up a periodical and not read about Stanley’s Snake Oil. The self-styled Rattlesnake King claimed to have “learned about the secret ancient formula of rattlesnake oil from Hopi medicine man,” Raden writes. “And that tracks, because Hopi medicine men definitely tell random trespassing white people stuff like that.”

Clark Stanley may not have invented snake oil, Raden argues, but he did pioneer the mass marketing of pharmaceuticals, to disastrous effect. His much-ballyhooed formula was mostly turpentine (!). But other patent medicines, which unlike snake oil were meant to be ingested, contained substances like cocaine, opium, mercury, lead, arsenic, and, incredibly, radium.

These proto-Goop concoctions were sold everywhere. Coca-Cola was marketed as a brain tonic, and it kind of was, because it had fucking cocaine in it. Many if not most tonics for premenstrual women and fussy babies contained heroin (which, to be fair, did help the cramps and calm the infants). Snake oil led to the nation’s first opioid crisis.

By 1893, William Randolph Hearst had already entered the field of newspaper publishing. His purchase of the New York Journal and subsequent poaching of the top talent at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World led to a “yellow journalism” arms race, with each publication trying to outdo the other with the luridness and font-size of its headlines: clickbait for the 19th century.

This came to a head in 1897, when Hearst, eager for a war with Spain because war is good for sales, dispatched the artist Frederic Remington to Spanish-controlled Cuba. “There will be no war,” Remington cabled his boss, to which Hearst famously replied: “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” A year later, the U.S. did indeed go to war with Spain, the appetite for which was catalyzed by Heart’s papers. (Remember the Maine?)

The Journal and the World are long gone, but people still read their competitor, which built its reputation on a promise made in 1897 to provide “all the news that’s fit to print”—and, implicitly, none that isn’t: the New York Times. Harrison, Cleveland, and William McKinley gave way to a president who was willing to take on big business: Theodore Roosevelt. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 mandated that anything containing alcohol, morphine, heroin, opium, cocaine, eucaine, chloroform, cannabis indica, chloral hydrate, and acetanilide had to say so on the package.

“The law,” Raden writes, “basically the No Roofies / No Duds Act of 1906, also strictly prohibited advertising the presence of any ingredients that were not present in the product—like actual snake oil in Stanley’s Snake Oil.” That drove the Rattlesnake King out of business, and created an enduring cliché.

True, Facebook and Fox News are more powerful than broadsheet print ads, the Times isn’t what it used to be, and if we want opiates, we have to get them from a doctor, a dealer, or a Sackler. But we’ve been here before. And what will deliver us from 2021 is the same thing that delivered us from 1893: the truth—with a big assist from the federal government.

https://gregolear.substack.com/p/selling-snak...v8iu8INI-A